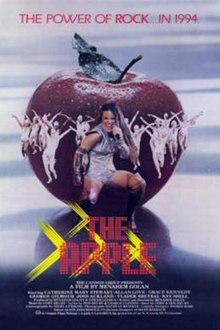

The Apple (1980 film)

| The Apple | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Menahem Golan |

| Screenplay by | Menahem Golan[1] |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | David Gurfinkel[1] |

| Edited by | Alain Jakubowicz[1] |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | The Cannon Group |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[4] |

The Apple (also called Star Rock) is a 1980 science fiction-musical film written and directed by Menahem Golan. It stars Catherine Mary Stewart as a young singer named Bibi, who, in a futuristic 1994, signs to an evil label named Boogalow International Music. It deals with themes of conformity versus rebellion, and makes use of biblical allegory[5] including the tale of Adam and Eve.

Principal photography took place in late 1979 in West Berlin. The film was panned by critics and has been considered to be one of the worst films ever made.[6][7]

Plot

[edit]In a cut[8]: 44:53–44:59 [9] two-song prologue of the film named "Paradise Day,"[8]: 41:06–41:13 [10] Mr. Topps (Joss Ackland) creates heaven and carves the first human, Alphie, out of a rock, sending Alphie to Earth to meet Bibi.[8]: 41:10–41:49 [8]: 42:31–42:36

The two take part in the 1994 Worldvision Song Festival. Despite being the most talented performers, they are beaten by BIM (Boogalow International Music) and its leader, Mr. Boogalow, who use underhanded tactics to secure a victory. The duo is approached by Mr. Boogalow to sign to his music label, but they soon discover the darker side of the music industry. Bibi is caught up in the wild lifestyle BIM offers, while Alphie risks his life to free her from the company's evil clutches. Alphie eventually convinces Bibi to run away with him, and the pair live as hippies for a year (and produce a child) before being located by Mr. Boogalow who insists Bibi owes him $10 million. Alphie and Bibi are saved by the Rapture, and all good souls are taken away by Mr. Topps who arrives on the scene in a flying apparition of a Rolls-Royce.

Cast

[edit]- Catherine Mary Stewart as Bibi Phillips

- Mary Hylan as Bibi's singing voice

- George Gilmour as Alphie

- Grace Kennedy as Pandi

- Vladek Sheybal as Mr. Boogalow

- Allan Love as Dandi

- Joss Ackland as Hippie Leader/Mr. Topps

- Ray Shell as Shake

- Miriam Margolyes as Alphie's landlady

- Derek Deadman as Bulldog

- Michael Logan as James Clark

- George S. Clinton as Joe Pittman

- Francesca Poston as Vampire / Star Rock / Mr. Boogalow's Receptionist / BiM band keyboard player / Lapmate at Mr. Boogalow's Penthouse Party

- Leslie Meadows as Ashley / Dancer

- Gunter Notthoff as Fatdog

- Clem Davies as Clark James

- Coby Recht as Jean Louis

- Iris Recht as Dominique

Finola Hughes, Femi Taylor, and John Chester in their film debuts as dancers

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Conception

[edit]

In 1975, Coby Recht, a successful Israeli rock producer, was signed to a major label for the first time, that being Barclay Records, which was founded and led by French producer Eddie Barclay.[11][8]: 17:35–17:39 As Recht described working with Barclay, "he really believed in me. But there was something there that I couldn't trust. I don't know why, but the guy looked to me like a villain."[11] His experience with Barclay, as well as being a "moral guy" who never liked what went on in show business, inspired the story of a musical Recht and his wife Iris Yotvat were conceiving for six weeks while in Paris,[8]: 41:10–41:49 [8]: 17:27–18:36 [11] and the antagonist Mr. Boogalow was based on Barclay.[11] Recht explained that it was "supposed to be 1984, but with music."[11]

Writing the musical in 1977,[12] Recht and Yotvat had 17 demos recorded before the first draft was even submitted to a company.[8]: 20:23–20:24 It was originally planned by Recht and Yotvat to be a Hebrew stage production, but the show "was so expensive that nobody could really raise it up for the stage," Recht explained.[11] He was then informed by a friend that filmmaker Menahem Golan was having a brief visit in Israel.[11] Recht had known Golan since he was nine, performing in shows at an Israeli-based children's theater where Golan directed.[11] Recht called Golan on a Friday for a face-to-face meeting about The Apple, which involved Golan spending four hours listening to demos of songs from the musical.[11] Golan finally decided to direct and produce a film version of The Apple, instructing Recht to be in Los Angeles immediately.[11] Yotvat said, "That was marvelous. That was just fantastic to think that it was going to be a movie all of the sudden. It was just amazing."[11]

Rewrites for the film and song translation

[edit]In 1979, Recht and Yotvat went to Los Angeles, where they resided in a villa that Golan offered,[8]: 20:48–20:58 while Recht occasionally went to Golan's house in Cheviot Hills to have meetings about the film.[8]: 21:44–22:00 Golan spent three weeks writing six screenplay drafts of The Apple.[8]: 22:04–22:15 According to Recht, Golan rewrote the story and all of the songs to the point where they were completely different from what Recht and Yotvat originally wrote,[8]: 21:10–21:24 which "frustrated" the two.[11] Golan's version of the plot was more comical and contradicted the Orwellian tone of the musical Recht originally envisioned.[8]: 25:30–26:06 Yotvat said that Golan was turning the script into "something that was kind of corny,"[11] and Recht stated Golan was making the story "out of touch" and "out of date."[8]: 21:08–21:09 He also disliked Golan's criticisms of Recht and Yotvat's plot not having any "action."[11] Recht said in a retrospective interview, "It's a small movie. It's rock and roll. And then he said to me, 'Eh…Rockin' Horse, Rock n' Roll.' So what can you do?"[11]

George S. Clinton, who had a previous career as a songwriter and recording artist, joined the project to translate the lyrics from Hebrew to English after being recommended for the job by Golan's secretary Kathy Doyle.[8]: 22:59–23:27 Clinton worked with Golan, Recht and Yotvat on the translations at Golan's house on afternoons.[8]: 24:14–24:19 Recht and Yotvat had a much more favorable time working with Clinton than with Golan, who translated the Hebrew lyrics into English.[11] As Recht explained, "working with George was great, I loved it because we were both lyricists."[11] After the translations were finished, the songs were tracked on a tape recorder and taken to Golan's home studio for the demos to be recorded, which Clinton sang on.[8]: 24:20–24:32

Auditions

[edit]

Approximately 50% of the demos for the English versions of the songs were finished by the time work on The Apple moved to London,[11] where two months worth of auditions, rehearsals, and recording and mixing of the score took place.[4][8]: 25:15–25:26 The auditions for The Apple were held at Turnham Green[12] for about a week, with around 1,000 people auditioning.[8]: 29:12–29:18 As Clinton described them, "We had auditioned a lot of different people, and it was crazy. I mean, people came from all over [the world] to be there, and there were so many people."[8]: 17:19–27:28 In fact, one of the people who auditioned for the film, who was from Wales, became so impatient while waiting that he yelled at Clinton and the other people auditioning to "finish the god damn song."[8]: 27:49–28:00

Around 200 people attended the dancer auditions, one of them Catherine Mary Stewart, a performing arts school attendee who was informed by the other students about the auditions.[4] Recht took particular notice of Stewart.[4] He recalled, "all of the sudden I saw her and I said to myself: This is Bibi. This is exactly what I had in mind when I wrote the script."[4] Stewart explained in a 2012 interview that while she had vocal training in her performing arts school, she didn't have the same "professional" singing skills of other members of the film's cast.[8]: 30:46–31:14 Despite this, Recht wanted her for the part of Bibi, and thus, she was cast for the role.[4] Recht described Stewart as "shocked" and "trembling all over" when she got the part.[4]

Recht lied to Golan that Stewart "was a great singer" to convince Golan to cast her Bibi.[4] Golan eventually noticed her poor singing, and he, as Stewart explained, "sent me to a voice coach who actually thought I was fine for the movie, but [the producers] kind of got cold feet."[4] Thus, Mary Hylan, a "terrific professional singer from L.A." as Stewart described her, served as Bibi's singing voice for the film.[4] Clinton first noticed Hylan singing at a Christmas party in 1978, and "she just blew me away," he recalled.[8]: 32:32–32:41

Filming

[edit]

According to Recht, he and Yotvat initially planned The Apple to cost $4 million to produce, "but when we were in London, Menahem [Golan] used to go like every week to Berlin and come back with another million. And then we got to $10 million."[4] This led Golan to shoot scenes with settings that looked bigger than what Recht wanted, which he was dissatisfied with.[4] Principal photography took place from September to December 1979 in West Berlin, where the production was moved in exchange for government subsidies from West Germany.[10][2] The Apple editor Alain Jakubowicz claimed that, as with Golan's previous works, the original footage was around 1 million feet long, or four hours worth, and "five to six" cameras were used to shoot the musical sequences.[4] The opening concert sequence was shot at the main hall of Internationales Congress Centrum Berlin[10] and was filmed for five days in a row.[8]: 55:59–56:11 The sequence for the track "Speed" was filmed at the Metropol nightclub, which held the Guinness World Record for biggest indoor laser show.[10] The outside hippie scenes were filmed at Schloss Park, located in Konigstrasse.[10] Some scenes in the film were shot in a factory that formerly produced poison gas during World War II.[13]

A majority of the extras for The Apple were students at Berlin American High School.[12] Ray Shell, who portrayed Shake and described making the film as "big fun," was replaced by a stunt double for his dancing shoots four times, and a scene for a song titled "Slip and Slide" was cut from the final product due to Shell's poor dancing.[12] Nigel Lythgoe and Ken Warwick served as choreographers for The Apple, Warwick featured in the film dancing in the sequence for "Coming."[13] Lythgoe described making The Apple as "really, really depressing on some days" and "very, very stressful," adding that most of the cast and crew "didn't really like the script. I mean, we really didn't."[13] Lythgoe and Warwick later both started working in singing competition shows like American Idol, which led to conspiracy theories by multiple people that The Apple predicted their later work.[13] Lythgoe shrugged these off: "There were a lot of singing competitions going on at the time. So it never really hit me that 'the search for talent' was Popstars and Pop Idol and American Idol, as much as just thinking that The Apple was kind of a Eurovision-style song competition.[13]

Conflicts between Golan and Recht took place when filming started; Recht was still in London mixing the songs, and Golan constantly made phone calls demanding him to be at the shoots in Berlin.[4] When he went to Berlin to go to the shooting location, the first thing he saw was Golan filming the uncut "Paradise Day" sequence[8]: 41:27–41:49 that took a million dollars alone to make:[4] "He was shooting this part that never ended up on the screen because it was terrible. It was terrible. There was like fifteen dinosaurs on the set. I couldn't believe my eyes."[4] The scene was filmed at an exterior location at CCC Film's Spandau Studios, a studio which was also used as the location for Boogalow's penthouse.[10] Joss Ackland, who portrayed Mr. Topps, recalled that the scene consisted of a combination of both real and "phony" animals[8]: 43:55–44:00 and the Mr. Topps character was in a crevice making Alphie and singing the song "Creation."[8]: 44:00–44:15 Multiple problems occurred shooting the sequence, such as the dinosaur pieces falling down and a tiger running from the set.[8]: 44:18–44:23 The uncut scene also involved both Mr. Topps and the devil character Mr. Boogalow doing a dance together, which involved Boogalow actor Vladek Sheybal falling on a river.[8]: 44:38–44:44

Post-production

[edit]Dov Hoenig was an editor for Golan's previous films and was initially planned to also be the editor of The Apple.[4] He also was on set with Golan on shooting days for the film.[4] Recht described him as his "spiritual partner," reasoning that he was the only person working on the movie that agreed with Recht and Yotvat's stylistic and production ideas.[4] However, Golan and Hoenig always had arguments with each other during the making of Golan's other works, and when working on The Apple, they nearly got into a fistfight.[4] It was by the time Hoenig suggested to Golan that a shot was "out of focus" that he fired him from the project.[4] This and the shooting of what Recht and Yotvat considered the film's "horrible" ending sequence is what persuaded the two to leave Berlin and go back to Israel.[4]

Jakubowicz replaced Hoenig's position and claimed in a retrospective that he enjoyed editing The Apple, especially the film's musical scenes.[4] However, he also described it as a "weird experience" due to the film's over-the-top nature and kitsch plot.[4] The Apple is edited in a fast-paced music video-esque manner.[8]: 58:10–58:20 According to Ackland, "Heaven was three quarters of the script. It was the whole point of the movie."[8]: 58:36–58:48 Cutting out most of the story's heaven aspects, including the "Paradise Day" scene, were Golan's methods of not going too "extreme" with the religious undertones in order for the film to be more "acceptable" and less "formidable" for audiences.[8]: 45:17–45:48 Yotvat suggested Golan's added comical elements of the story was also due to his focus on the film's accessibility.[8]: 48:13–48:30 Jakubowicz later edited another musical film Golan worked on, an adaptation of The Threepenny Opera (1928) named Mack the Knife (1989).[4]

Music

[edit]The recording and mixing of The Apple's score took place at The Music Centre, a studio in Wembley,[14] and cost an "amazing budget" to complete, Recht said.[8]: 33:10–33:14 Richard Goldblatt served as the audio engineer.[14] The tracks were remixed to Dolby Stereo on a Neve console for the film by The Village Recorder, the only studio Recht could find that had a Neve.[8]: 35:04–35:58 The studio charged $7,000 a day for remixing the tracks, and Golan sent a messenger to give the studio money.[8]: 35:34–35:46 The Apple's soundtrack features sounds and production techniques that were never heard on any other record before, such as the use of pink noise on the snare drums.[8]: 36:06–36:16 The London Philharmonic Orchestra performed the orchestral arrangements for both the songs and score for the film.[8]: 36:18–36:40 Clinton served as the conductor and was initially "scared shitless" as it was his first time conducting a full professional orchestra.[8]: 36:40–36:54 Instead of a baton, he conducted the orchestra with chopsticks he received from a Chinese restaurant that was two buildings away from the studio where the soundtrack was recorded.[8]: 36:55–37:07

Recht recalled one of the sessions having more than 200 people, including several musicians and a choir consisting of 120 vocalists.[8]: 33:25–33:48 Recht said recording the film's reggae number "How To Be a Master" was complicated due to actual Jamaican musicians performing on the song and not being able to "read the charts" that were in English.[8]: 33:52–34:14 According to Clinton, Grace Kennedy, who played Pandi, had an uncomfortable time singing "Coming," so Clinton had to tell her that it was her character singing the lyrics and not Kennedy.[8]: 37:29–34:44

The musical numbers are as follows:

- "BIM" - Pandi, Dandi

- "Universal Melody" - Bibi, Alphie

- "Made for Me" - Dandi, Bibi, Chorus

- "Showbizness" - Boogalow, Shake, Chorus

- "The Apple" - Dandi, Chorus

- "How to Be a Master" - Boogalow, Shake, Chorus

- "Speed" - Bibi, Chorus

- "Where Has Love Gone" - Alphie

- "BIM" (Reprise) - Bibi, Chorus

- "Cry for Me" - Bibi, Alphie

- "Coming" - Pandi

- "I Found Me" - Pandi, Bibi

- "Child of Love" - Hippie Leader, Bibi, Alphie

- "Universal Melody" (Reprise) - Cast

A soundtrack album was released by Cannon Records in 1980.[15] Versions of several songs on the album ("Coming", "Showbizness", "Master" and "Child of Love") differ substantially from those used in the film, and Joss Ackland's song "Creation" (a variation of "Universal Melody") didn't make the final cut.

The album never officially has been issued on CD. Yma Sumac is often wrongly credited with the film,[16] but she did not appear in it nor was her music used.

- "BIM" – Grace Kennedy & Allan Love

- "Universal Melody" – Mary Hylan & George Gilmour

- "Coming" – Grace Kennedy

- "I Found Me" – Grace Kennedy

- "The Apple" – Allan Love

- "Cry for Me" – Mary Hylan & George Gilmour

- "Speed" – Mary Hylan

- "Creation" – Joss Ackland

- "Where Has Love Gone?" – George Gilmour

- "Showbizness" – Vladek Sheybal & Ray Shell

- "How to Be a Master" – Vladek Sheybal, Grace Kennedy, Allan Love & Ray Shell

- "Child of Love" – Joss Ackland, Mary Hylan & George Gilmour

Themes

[edit]Described by Francis Rizzo of DVD Talk as the Faust legend told through the lens of the music industry,[17] The Apple is about a conflict between good and evil, a battle between the pacifistic hippies and show business people who only care about wealth and power.[11] Journalist Richard Harland Smith [who?], likening The Apple to a "Christian scare film," compared the story to Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf (1925) and its ending to the Nazi's Final Solution;[18] Smith wrote that the film involves a homophobic protagonist Alphie who is trying to save his "normal" relationship with Bibi from what the film considers satanic, which includes electronic music, glitter, homosexuals, and drag queens.[18]

Release and reception

[edit]Stewart described how Golan predicted the success of The Apple:

Menahem was very passionate about what he was doing. He had very lofty ideas about the project. He thought this was going to break him into the American film industry. It had, you know, all the elements that he thought were necessary at that time. It was the early eighties and there were a lot of musicals. And Menahem thought that was his ticket into the American film industry.[4]

The Apple made its premiere as the opener of the 1980 Montreal World Film Festival, where its attendees received vinyl records of music from the film; the festival's president Serge Losique was recommended by his son to screen the movie.[4] According to Jakubowicz, there were "bad reviews almost everywhere."[4] The movie garnered a largely negative audience at the festival, some watchers throwing the vinyl records at the screen.[4] According to Stewart, Golan was so distraught from this that after the festival, he considered killing himself by jumping off a hotel balcony.[4] As Golan once said, "It's impossible that I'm so wrong about it. I cannot be that wrong about the movie. They just don't understand what I was trying to do."[4]

Common criticism from both reviews that appeared in trade publications and major news outlets and the audience were a lack of originality,[2] a weak script,[2] uninspired music,[2] poor execution,[2] and Golan's inexperienced take on the 1960s hippie movement.[4] Variety gave a negative review of the film, stating that "the characters and story are flimsy and seem intended as mere pegs on which to hang the musical numbers" and that "the choreography generates a lot of energy, but its frantic tempo doesn't always compensate for lack of imagination." However, the review also complimented the film's technical aspects, particularly that "David Gurfinkel's camera work profusely [uses] every trick in the business, every filter and lighting device, to hold attention up at all times."[citation needed] The Monthly Film Bulletin described The Apple as a "cut-price extravaganza [that] plummets to a new low in opportunistic inanity," and said that the "sole saving grace is an enthusiastically camp performance by Vladek Skeybal."[19] The Ottawa Citizen described The Apple (along with Golan's earlier film The Magician of Lublin) as containing "remarkable feats of ineptitude".[20] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 27% score based on 11 reviews, with an average rating of 4/10.[21] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 39 out of 100, based on 5 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews".[22]

At the 1980 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards, the film was nominated for Worst Picture. According to Stinkers founder Mike Lancaster, The Apple was technically the worst movie of the year—and the worst he had ever seen—but its profile was too low to really warrant winning the award. Instead, Worst Picture went to Popeye. The ballot was revised and re-released in 2006, where the Worst Picture results remained the same. In addition, the film received six more nominations, two of which were wins: Worst Director (Golan) and Least “Special” Special Effects. Its other four nominations were for Worst Screenplay, Worst Song (both “B.I.M.” and “Universal Melody”), and Most Intrusive Musical Score.[23]

From retrospective reviews, Eric Henderson of Slant magazine gave The Apple one star out of four and said "every song in the goddamned movie sucks" and added that the film's "relentless bad taste is sure to appeal to the same audience that won't even realize they're being slapped in the face".[24] TV Guide stated "The Apple clearly was designed to duplicate the success of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and failed dismally, in large part because the music is so stupendously banal...The lesson: Making a cult hit is harder than it looks."[25] Sean Burns in the Philadelphia Weekly gave the film a scathing review: "The Apple isn't just the worst disco musical ever made; it could very well be the worst movie ever made, period."[7] Bill Gibron of DVD Verdict described The Apple as "a gamy glitterdome of outrageous kitsch passing itself off as a futuristic fable."[26] Gibron strongly criticised the film's music, saying "Lines fail to rhyme, emotions are so spelled out that inbred invertebrates can figure out the meaning, and everything feels like it was produced by Georgio Moroder's [sic] insane brother...The Apple should be a celebration of all that is camp. Instead, it's just seriously disturbed."[26]

However, articles about the film's 2017 Blu-ray release were much more favorable towards The Apple. Austin Trunick honored it as "the perfect sort of cult film – unintentionally campy, with an insane premise, great production value, and memorable songs – that most people, once they've seen it, spend the rest of their movie-loving lives trying to get it in front of as many other people as possible."[27] Rizzo praised it as an example of "a filmmaker trying to do too much and attempting to punch above their weight, rather than doing the lazy, same-old thing."[17] He concluded, "It may not be a great (or even good) movie, but The Apple is certainly an experience, one that any fan of wondrously bad cinema or over-the-top musicals will suffer gladly, luxuriating in its wacky vision of the then-future and idiosyncratic tale of good versus evil."[17] Flavorwire claimed "True bad movies carve out their own worlds. The Apple seems to have come from another universe entirely – and God bless it for that."[5] They reasoned, "all through The Apple, everyone is just going for it, full-throated, even though the songs are shit and the sets are cheap and the effects are worse. But you get the sense that you couldn't have told them any of that. Whatever Golan had, it was something everyone involved was snorting (literally or figuratively)."[5]

Alternate version

[edit]In 2008, there was a mix-up booking the print for a screening at The Silent Movie Theatre in Los Angeles, so MGM sent over uninspected reels marked "Screening Print."[28] Presumably this was an original preview print, as it included additional scenes that were cut out of the widely released version (including the complete Coming and Child of Love musical sequences which had been truncated in the final print), a simpler entrance for Mr. Topps at the end (instead of exiting from a Rolls-Royce, he merely transforms from the previously seen hippie leader), and the closing credits were presented in a different font and layout.[28] This version was screened a few times at The Silent Movie Theatre,[28] and it ran at Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in August 2008.[29]

Home media

[edit]The Apple was released on a Region 1 DVD by MGM Home Entertainment on August 24, 2004. Scorpion Releasing under license from MGM, released the film onto Blu-Ray in 2017 which featured a brand new 2016 HD master, audio commentary by star Catherine Mary Stewart moderated by film historian Nathaniel Thompson, On Camera Interview with star Catherine Mary Stewart, and Original Theatrical Trailer. On April 17, 2013, the film was released as a video on demand from RiffTrax. This edition of the film features a satirical commentary done by the former stars of Mystery Science Theater 3000 - Michael J. Nelson, Kevin Murphy, and Bill Corbett.[30]

See also

[edit]Films released during the late 1970s disco and jukebox movie musical craze

[edit]- Car Wash (1976)

- Saturday Night Fever (1977)

- Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978)

- Thank God It's Friday (1978)

- Skatetown, U.S.A. (1979)

- Roller Boogie (1979)

- Xanadu (1980)

- Can't Stop the Music (1980)

- Fame (1980)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Star Rock". Filmportal.de. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Apple". AFI Catalog. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "The Apple". British Board of Film Classification. December 12, 1980. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Harris, Blake (February 5, 2016). "The Apple Oral History: How Did This Get Made". /Film. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c Bailey, Jason (July 11, 2017). "Bad Movie Night: The Distinctive Disco Cheese of 'The Apple'". Flavorwire. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ Brownfield, Troy (August 7, 2020). "The Worst Movie Musicals Ever". The Saturday Evening Post. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Burns, Sean (July 12, 2006). "Summer Camp". Philadelphia Weekly.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq White, Mike (January 18, 2012). "Episode 46: The Apple (1980)". The Projection Booth (Podcast). BlogTalkRadio. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ McCoy, Dan (February 3, 2018). "Episode #250 – The Apple". The Flop House (Podcast). Maximum Fun. Event occurs at 1:04:54–1:05:55. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Apple Movie Filming Locations". Fast Rewind. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Harris, Blake (5 February 2016). "How Did This Get Made: The Apple (An Oral History)". /Film. p. 1. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Behind the Scenes of The Apple Movie". Fast Rewind. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Parker, Lyndsey (November 16, 2015). "Nigel Lythgoe on His Disco Cult Movie, 'The Apple': 'The Best Part of Making It Was Finishing It'". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ a b The Apple: The Original Soundtrack Of The Musical Film (1980) (Back cover). Various Artists. Cannon. C1001.

- ^ "Soundtrack Details: Apple, The". SoundtrackCollector. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ "Apple, The". sunvirgin.com. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c Rizzo, Francis (June 20, 2017). "The Apple (Blu-Ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Harland Smith, Richard. "The Apple (1980)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Pulleine, Tim (1982). "Star-Rock". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 49, no. 576. London: British Film Institute. p. 137.

- ^ Labonte, Richard (November 28, 1981). "Kung Fu Film Flops". The Ottawa Citizen. p. 39.

- ^ "The Apple (1980)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Apple (1980) reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ "Past Winners Database". August 15, 2007. Archived from the original on August 15, 2007.

- ^ "The Apple Review". Slant. August 24, 2004. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ "The Apple". TV Guide. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Gibron, Bill. ""The Apple" Review". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on September 21, 2004. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ Trunick, Austin (June 27, 2017). "The Apple". Under the Radar. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ a b c Jensen, Lucas (December 11, 2008). ""The Apple": The Lost Footage, Revealed". Idolator. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Austin - The Apple". Vice. August 14, 2008. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Now Available on VOD from RiffTrax…". Satellite News. April 16, 2013. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

External links

[edit]- The Apple at IMDb

- The Apple at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Apple at Metacritic

- The Apple at The 80's Movie Rewind site.

- The Apple at the MGM Movie Database.

- 1980 films

- West German films

- 1980s English-language films

- English-language German films

- 1980s science fiction comedy films

- 1980s musical comedy films

- American science fiction comedy films

- American musical comedy films

- Cultural depictions of Adam and Eve

- Films about drugs

- Films about music and musicians

- Films directed by Menahem Golan

- Films set in the future

- Films set in 1994

- Films shot in Berlin

- Films scored by George S. Clinton

- Science fiction musical films

- Golan-Globus films

- 1980 comedy films

- Films produced by Menahem Golan

- Hippie films

- Films about the rapture

- Films with screenplays by Menahem Golan

- Films produced by Yoram Globus

- 1980s American films

- 1980 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction comedy films

- English-language musical comedy films

- 1980 musical films