St. George, Louisiana

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (April 2024) |

This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (May 2024) |

St. George | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | East Baton Rouge |

| Incorporated | October 12, 2019 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dustin Yates |

| • City Council | Steven Monachello, Dist. 1 Ryan Heck, District 2 Max Himmel, District 3 Richie Edmonds, At-Large Patty Cook, At-Large |

| Population (2019) | |

• Total | 86,316 |

| Time zone | UTC-6:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5:00 (CDT) |

| Website | Official website |

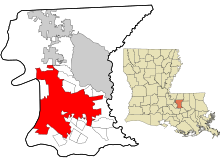

St. George is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana's East Baton Rouge Parish. It has a population of 86,316 and is the fifth most-populous city in Louisiana.

St. George is the newest incorporated city in Louisiana and was approved in a ballot initiative on October 12, 2019.[1] Upon incorporation, it became the second largest city in East Baton Rouge Parish.[2][3] The city originated from a previously unincorporated area of East Baton Rouge Parish located southeast of the City of Baton Rouge.[2][4]

A legal action[5] to challenge the incorporation[6] of St. George was filed in 19th Judicial District Court in East Baton Rouge Parish on November 4, 2019. After rulings by both the 19th Judicial District Court[7] and the Louisiana First Circuit Court of Appeals,[8] the Louisiana Supreme court upheld incorporation by a 4-3 decision.[9][10]

History

[edit]

Native American presence

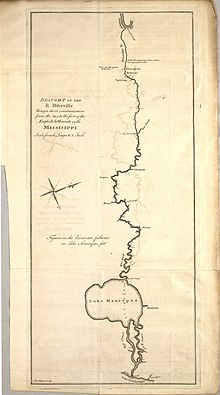

[edit]After the French and Indian War ended in 1763, Bayou Manchac (originally known as Rivière d'Iberville or the Iberville River) became an international border between the British (West Florida) and Spanish (Isle of Orleans) colonial territories. This bayou (which now marks the southern border of the City of St. George) runs from the Mississippi River on the west to the Amite River on the east.

Native Americans, specifically Choctaw, were known to have lived in southeast Louisiana when Europeans first arrived.[11] In 1764, after encroachment from European settlers, the Alabama-Coushatta and Pakana Muscogee Indians migrated into Louisiana, to just north of Bayou Manchac.[12]

American Revolution

[edit]In 1765, the British built Fort Bute on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River at Bayou Manchac, not far from the present-day University Club Golf Course. The fort consisted of a blockhouse and stockade capable of holding 200 men.[citation needed]

On May 8, 1779, Spain officially entered the American Revolutionary War by declaring war against the British. With this news, Bernardo de Galvez, the colonial Governor of Spanish Louisiana, began assembling an ad hoc army of over 1400 Spanish regulars, Acadian militia,[13] free men of color and native Americans.[citation needed] On August 27, 1779, they began advancing toward Baton Rouge. Trudging through muddy swamp at a rate of nine miles a day, they arrived at Fort Bute eleven days later.[citation needed] After a brief skirmish, they captured and demolished the fort in what would become the first Spanish action against the British during the American Revolutionary War. Galvez and his army remained at Fort Bute for six days before moving on to defeat the British garrison at Fort New Richmond in the Battle of Baton Rouge (1779).[citation needed] Their victories at Fort Bute and Fort New Richmond helped to clear the Mississippi River of British forces and put the lower Mississippi River under Spanish control.[citation needed]

War of 1812

[edit]During the War of 1812, U.S. Gen. Andrew Jackson had the mouth of Bayou Manchac filled with earth to prevent the British from using it to launch a surprise attack on New Orleans. In 1828, American settlers reinforced that blockage with a large earthen dam to stifle flood waters from regularly inundating their properties. Although it was later suggested that reconnecting the two bodies of water might actually help alleviate flooding in the area, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers declined to.[14]

Village St. George

[edit]Between 1956 and 1968, the Village St. George subdivision was constructed[15] near its namesake, later forming the nucleus of the census-designated place (CDP) of the same name.

In 1966, the increased suburbanization of the area warranted the creation of the "Village St. George Volunteer Fire Department and Social Club", now called the St. George Fire Protection District. Its coverage area also overlapped with much of the new city's boundaries.[16]

Place names

[edit]

Prominent place names in the St. George area include:

- Amite River: Possibly from the French amitie ("friendship") or Choctaw himmita ("young")[17]

- Baton Rouge: Le bâton rouge (French for "the red stick") is a translation of Istrouma, possibly a corruption of the Choctaw iti humma ("red pole")

- Bayou Manchac: From Choctaw expression for "rear entrance" (i.e., to Lake Pontchartrain)[18]

- Essen Lane: Named by ethnic Germans in the area after a city in Germany[citation needed]

- Highland Road: From the "Dutch [i.e., German {Deutsch}] Highlanders," a colony of Pennsylvania German farmers who settled along the bluffs that overlook the Mississippi River floodplain at Highland Road[citation needed][19]

- Kleinpeter Farms Dairy: From the name (literally, "short [or young] Peter") of a prominent early German family in the area[citation needed]

- Mississippi River: From the French (Messipi) rendering of the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe or Algonquin) name for the river (Misi-ziibi), meaning "Great River"[20]

- Nicholson Drive (Louisiana Highway 30): Named for James W. Nicholson, Civil War veteran and former president of Louisiana State University (1883–1884 and 1887–1896)[21][22]

- Perkins Road: Named for twin brothers from Kentucky who owned sugar plantations in Baton Rouge[23]

- Siegen Lane: Named by ethnic Germans in the area after a city in Germany[citation needed]

- Staring Lane: From the name of a prominent early German family in the area[citation needed]

Recent history

[edit]Incorporation efforts

[edit]In 2012 and again in 2013, St. George organizers[24] sought approval of the state legislature to form a new school district but were unsuccessful.[25] In June 2015, organizers attempted to form a new city but failed to collect enough signatures[26] (71 short of the minimum 17,859 required) on the petition (at least 25 percent of electors residing in an area proposed for incorporation is needed).[27] Consequently, an election could not be called.[28][29] The formation of a new city is seen as a pathway for forming a new school district.[30] The formation of a new school district would require approval of the state legislature as well as approval of voters at the state level and approval of voters in East Baton Rouge Parish.[31]

In October 2018, St. George organizers submitted a second petition to form a new city.[32] This petition proposed a smaller city that included some of the same area.

In February 2019, the East Baton Rouge Parish Registrar of Voters declared that the petition had enough valid signatures (at least 12,996 required; 14,585 accepted) to meet the requirements for eligibility.[33] In March 2019, Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards authorized adding the petition to the October 12, 2019 ballot.[34]

Of the more than 54,000 registered voters living in the St. George area, approximately 32,293 (60%) cast ballots, with 17,422 (54%) voting in favor of incorporation.[35][36]

However, before the Governor could appoint[37] an interim mayor and interim city council, a legal action[5] was filed to contest the incorporation.

On June 12, 2020 Governor John Bel Edwards signed SB243, authored by Senator Bodi White and Representative Rick Edmonds, into law as Act 361 of the 2020 Regular Session of the Louisiana Legislature.[38] The St. George Transition District creates a framework for the transition of taxing authority and services from East Baton Rouge Parish to the City of St. George.[39]

According to the Act, the St. George Transition District would not be granted proper authority until the lawsuit challenging the incorporation of the City of St. George was proven unsuccessful.

Legal proceedings

[edit]Relief sought by the plaintiffs included a favorable judgement denying the incorporation of St. George, or, alternatively, a parish-wide election to determine if the Plan of Government should be amended to allow for the formation of a new city. Plaintiffs also requested that the court hold defendants responsible for the costs of litigation.

19th Judicial Court

[edit]The May 31, 2022 ruling by the 19th Judicial Court was based on state law governing "Legal action contesting an incorporation":

If the district court determines that the provisions of this Subpart have not been complied with, that the proposed municipality will not be able to provide the public services proposed in the petition within a reasonable period of time, or that the incorporation is unreasonable, the district court shall enter an order denying the incorporation. La. R.S. 33:4(E)(2)(a)

The judgment addressed many issues in the trial, including:

- Whether the municipality can in all probability provide the proposed public services within a reasonable period of time. The Court ruled that "the Incorporators, if properly funded, could in all probability provide some of the proposed public services within a reasonable period of time…. However, it is doubtful that [the other services listed in the petition for incorporation] can be provided without increasing taxes…. Their petition did condition the providing of some services if funds were available." (pp. 6–7)

- Whether the incorporation of St. George is reasonable. "Based on the evidence, the City of St. George would run a deficit of approximately $3 million dollars on day one and this excludes the additional cost of the Sheriff. This deficit will be a huge negative on the City of St. George. St. George is required to run a balanced budget and because of this deficit there would be layoffs and a reduction in public services" (p. 8)

- Whether the Incorporation may adversely impact other municipalities in the vicinity. The Court determined that "If St. George were to incorporate, the [Baton Rouge municipal budget] general fund would further be reduced by $48 million dollars[,] leaving the City of Baton Rouge with a 45% cut in its budget."[40] $51 million dollars represents only a 4.95% reduction in the total budget, and only a 15.47% reduction in the 329.5 million dollar general fund listed.) (p. 9).

Louisiana First Circuit Court of Appeal

[edit]The First Circuit Court ruling on July 14, 2023, included the following judgements:[41]

- Insufficient plan. "We affirm the June 13, 2022 judgment of the trial court denying the incorporation," the First Circuit Court said, "because the petition failed to comply with the requirements of La. R.S. 33:1(A)(4)." (p. 25) This section includes the following requirement: A listing of the public services the municipal corporation proposes to render to the area and a plan for the provision of these services. The court said that "although the petition listed the services that would be provided, the petition did not provide ... a plan for the provision of those services." (p. 25) The court also held that a statement in the petition that “services will be provided subject to the availability of funds derived from taxes, license fees, permits, and other revenue which becomes available to the municipality and are authorized by state law' does not constitute a plan for the provision of those services as required by La. R.S. 33:1." (p. 25)

- Lack of standing. The court determined that two of the plaintiffs did not have standing, and were dismissed from the lawsuit. Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome, according to the court, was not an elected official of the governing authority; therefore, lacked standing. (pp. 2 and 25). The court also determined that Baton Rouge resident, M.E. Cormier lacked standing, citing her residency outside of the proposed city limits did not give her an actual interest, nor would she be adversely affected by the incorporation of St. George. (p. 4)

- Dismissal of other issues. Because the petition was deemed to be out of compliance with the requirements, the court held that any discussion of other issues ("including the alleged unreasonableness of the incorporation and the alleged adverse impact on the City of Baton Rouge") would not be considered (p. 25).

A spokesman for the City of St. George said the matter would be appealed to the Louisiana Supreme Court.[42]

Louisiana State Supreme Court

[edit]The Supreme Court Ruling on April 26, 2024 affirmed the incorporation of the City of St. George in a 4-3 decision. This ruling directly addressed the issues of Baton Rouge in the following points

- Does incorporation affect an existing city within three miles? "Also, the statute does not limit the adverse impact factor to economics. Evidence shows that Baton Rouge can actually be positively affected by St. George’s growing population. Those people and their money will stay in the parish. This increases revenues and improves quality of life across the parish. This factor favors incorporation."

- Will incorporation affect the interest of landowners in the affected area? "Landowners and residents of St. George will benefit by their sales tax revenue being used on needs specific to St. George. Again, because of the nature of the consolidated City-Parish government, Baton Rouge has arguably experienced a windfall by collecting taxes in St. George without returning proportionate money and services. Incorporation will allow the money paid by St. George citizens to stay in St. George. This factor favors incorporation."

- Is the cost of operating the municipality prohibitive? "This factor is previously analyzed under the ability to provide public services within a reasonable period of time. We find St. George’s revenue will cover its operating costs. This factor favors incorporation."

The concluding statement of the courts' opinion included the following statement:

"Despite the challenge, we conclude St. George can provide public services within a reasonable period of time. Applying objective factors to determine reasonableness, we hold incorporation is reasonable. We reverse the lower courts’ denial of incorporation and render judgment in favor of Proponents."[10]

Annexations

[edit]

Prior to the incorporation of St. George, any property owner in unincorporated areas adjacent to the Baton Rouge city limits could request to be annexed into the city of Baton Rouge.[43] The request for annexation must be submitted to the Metro Council for approval.[44]

During the first petition effort, several residents and business owners annexed into the Baton Rouge city limits (viz., Baton Rouge General Medical Center – Bluebonnet Campus,[45] Celtic Media, Costco, L'Auberge Casino & Hotel Baton Rouge, Mall of Louisiana,[46] Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center,[46] Siegen Lane Marketplace and the residential neighborhood Legacy Court).

Following the October 12, 2019, election, additional residents[47] and business owners[48] in the proposed St. George city limits requested annexation into the City of Baton Rouge (viz., One United Plaza, Two United Plaza, Four United Plaza, Eight United Plaza, Twelve United Plaza, United Plaza III, Lipsey's[49] and Turner Industries[50]).[51][52][53] On January 8, 2020, the Metro Council approved all of these annexations.[54]

On February 7, 2020, St. George organizers filed a lawsuit seeking to invalidate the annexations in the United Plaza area. The lawsuit claims that the legal requirements for these annexations were not followed.[55][56][57] An attorney who represents the property owners claims that the lawsuit is without merit.[58] Annexation petitions requested following the certification date of the October 12, 2019 election to incorporate the City of St. George could possibly be declared null and void since the City of Baton Rouge at that date lacked the authority to annex any properties within the boundaries of St. George established in the State of Louisiana approved petition to incorporate as authorized by Title 33 of Louisiana law.[59]

On February 26, 2020, the Metro Council approved additional annexations into the City of Baton Rouge (viz., Louisiana State Employees Retirement System, Teachers Retirement System of Louisiana and Two Sisters of Baton Rouge).[60]

Geography

[edit]Area

[edit]The city covers approximately 60 square miles[2] and be located entirely within the southeastern section of East Baton Rouge Parish, bordered on the west by the Mississippi River, on the south by Bayou Manchac, and on the east by the Amite River. Much of the northwestern boundary of the city would extend to the Baton Rouge city limits, although portions of St. George would border unincorporated parish land.[61]

Flooding

[edit]The 2016 Louisiana floods had a profound effect upon East Baton Parish, particularly along the Comite River, the Amite River and Bayou Manchac.[64] In response, East Baton Rouge Parish developed a Stormwater Master Plan Implementation Framework to mitigate flooding concerns.

In 2018, Congress authorized funding for the East Baton Rouge Parish Flood Risk Reduction Project to reduce flooding throughout the parish.[65] Using $187 million in federal funds and $64 million in matching state and local funds, the project will provide for 66 miles of drainage improvements along five sub-basins in the parish (see interactive map of the EBR Flood Risk Management Project). In the St. George area, the authorized four-year projects involve:

- Jones Creek and tributaries: clearing and snagging three miles and structurally lining 16 miles with reinforced concrete ($148.5 million)

- Ward Creek and tributaries: clearing and snagging 14 miles of channel and concrete lining ($20.5 million)

- Bayou Fountain: clearing and widening 11 miles of channel ($13 million)

Organizers of the City of St. George have budgeted $2,247,000 in Year 1 for drainage and transportation.[66] This accounts for just over 1 percent of the proposed costs.

Baton Rouge fault

[edit]The Baton Rouge fault is an active growth fault that runs across the southern part of East Baton Rouge Parish, including parts of the St. George area.[67] It extends from the Mississippi River near downtown Baton Rouge to the Amite River. In the St. George area, it generally runs along Tiger Bend Road from Airline Highway (Highway 61) to the Amite River. The height of the escarpment ranges from 4 to 7 meters. The average rate of vertical movement is about 3–5 mm/year.[68] The fault has had a particularly pronounced effect near the Jones Creek Road-Tiger Bend Road intersection.[68] Continuous structural repairs to Woodlawn High School buildings located at that intersection forced the abandonment of the property and the building of a new school complex in Old Jefferson—the first new campus that the school board built in the parish in more than thirty years.[69] In 2017, several residents from the Tiger Bend area raised concerns[70] about plans for an upscale subdivision located near the fault line.[71]

Geomorphology

[edit]A Pleistocene prairie terrace, formed of alluvial deposits and wind-blown soil (Peoria loess), underlies most of East Baton Rouge Parish.[72][67] In the St. George area, long slopes along portions of Highland Road can be seen where the prairie terrace meets the Mississippi River floodplain.[73] Visitors to the LSU Hilltop Arboretum, for example, must drive up the slope to enter the facility.

Government

[edit]Appointment of the interim government

[edit]According to Louisiana Revised Statute Title 33, Section 6 - Officers of newly incorporated municipality:

"The governor shall appoint all the officers of a newly incorporated municipality, who shall give bond as required. Such officers shall hold office until, the next general municipal election and until their successors take their oaths of office."[74]

Appointment of city officials

[edit]On May 14, 2024, following the Louisiana Supreme Court's decision to reverse the lower courts' ruling, thus allowing the incorporation of the City of St. George, governor Jeff Landry appointed Dustin Yates to be the interim mayor and Todd Morrison to be the police chief.

On May 23, 2024, Landry appointed the following members to serve as aldermen for the city of St. George.

- District 1: Steven Monachell

- District 2: Ryan Heck

- District 3: Max Himmel

- At-large: Richie Edmonds

- At-large: Patty Cook

Transition district officers

[edit]Following the Louisiana Supreme Court's April 2024 decision overturning the lawsuit challenging the incorporation of the City of St. George, the St. George Transition District now had the necessary authority to proceed with duties outlined in Act 361 of the 2020 Regular Session of the Louisiana Legislature.[75] The first act was to elect officers. The officers elected included: J. Andrew Murrell as Chairman, Norman Browning as Vice Chairman, Chris Rials as Treasurer, Jim Talbot as a District Member, and William Potter as Secretary. Browning, Rials, Murrell, and Talbot were heavily involved in the petition efforts to incorporate, while Potter was recommended to serve by East Baton Rouge Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome. The transition district then approved a motion to request that East Baton Rouge Parish transfer a 2% sales tax revenue to the St. George Transition District. The transition district also voted to approve the opening of a bank account at Hancock-Whitney Bank, and approved the motion to headquarter the transition district out of the interim city hall located at the St. George Fire District Training Academy.[76]

Census-designated places

[edit]

The city of St. George includes six of the seven Census-designated places (CDPs) south of Baton Rouge in East Baton Rouge Parish:

The seventh CDP, Gardere, chose against joining the new city in the first petition effort.

Parks and recreation

[edit]The St. George area is served by the Recreation and Park Commission for the Parish of East Baton Rouge (BREC).[77] Park facilities in the St. George area include the Burbank Soccer Complex, the Highland Road Community Park, Highland Road Park Observatory, Santa Maria Golf Course, and Airline Highway Park.

Through BREC's Capital Area Pathways Project (CAPP), a network of connected trails and greenways is being developed throughout the parish.[78] BREC's Blueways initiative provides paddling access to Bayou Fountain from Highland Road Community Park. Additional canoe-kayak launches are planned for Bayou Manchac and Ward Creek.[79]

The LSU Hilltop Arboretum is a 14-acre museum showcasing an extensive collection of Louisiana native trees and shrubs. It includes a pond with an elevated wooden boardwalk and trails through more than 150 species of Southern native trees, shrubs and wildflowers. A new feature is a wildflower meadow with an earthen amphitheater.[80] A historic marker near the pond helps to identify the route of pioneering Philadelphia naturalist William Bartram (1739–1823) through eight southern states, including Louisiana.[81]

Historic sites

[edit]The National Register of Historic Places includes several sites in the St. George area. Among them are:

- Audubon Plantation

- Les Chenes Vertes ("Live Oaks")[82]

- Lee Site Archeological Site (access restricted[83])

- Ory House[84]

- Santa Maria Plantation[85]

- Sara Peralta Archeological Site (access restricted[83])

- Willow Grove

- Woodstock Plantation[86]

Other sites of historical interest in the St. George area include:

- Burtville: Founded ca. 1887, Burtville was a logging town located on Nicholson Drive (Louisiana Highway 30).

- Fort Bute: The original site lies beneath the Mississippi River.

- Hoo Shoo Too Club: The fishing lodge of the all-male Hoo Shoo Too Club (established in 1885), was located along the banks of the Amite River.[87]

- Jefferson Highway: The historic Jefferson Highway was designated in 1916. It runs through from New Orleans, Louisiana, to Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.[88]

- Old Hickory Lodge:[89] Believed to have been built in 1814 as a Masonic Lodge, the Old Hickory operated as a private social club at the intersection of Jefferson Highway and Tiger Bend Road.

- St. George Catholic Church: Founded in 1908,[90] the church was the second Catholic church in East Baton Rouge Parish, after the downtown Baton Rouge church that would eventually be designated as St. Joseph Cathedral. The church parish's original boundaries were similar to the City of St. George's city limits, providing the area with an early sense of continuity.[2] At present, it remains prominent in the area as the second-largest parish within the Diocese of Baton Rouge,[91] along with its new 1,200-seat church building at Siegen Lane.[90]

Education

[edit]Proposed school district

[edit]The incorporation effort for St. George began with a goal of creating a new school district independent of the East Baton Rouge Parish School System.[92][3]

To form a new school district, however, the new city must first be established.[93] So a new school district was not on the petition or ballot for the formation of the City of St. George.[94][34]

The process for establishing a new school district in the St. George area would require several steps:[95]

- Authorize constitutional amendment: The Louisiana State Constitution would need to be amended to allow the new school district to access state education funds and to give the City of St. George authority to levy local property taxes.[96] Authorization in the state legislature for a statewide referendum on a constitutional amendment would require support of two-thirds of both the House and the Senate.

- Establish boundaries: The state legislature, in a simple majority vote, would need to approve the map of the area to be served by the proposed St. George school district. The boundaries could extend beyond the boundaries of the City of St. George.[97]

- Obtain voter approval: A statewide referendum would need to be held to approve of the constitutional amendment. A majority of voters in the state as well as a majority of voters in East Baton Rouge Parish would need to approve the constitutional amendment for it to become law.[31]

All of these steps would need to occur before a new school district could be formed.

Informal education

[edit]Facilities in the St. George area[61] that provide opportunities for informal education include:

- Highland Road Park Observatory

- Jones Creek Regional Branch Library

- LSU Hilltop Arboretum

Transportation

[edit]There are no east–west roads that run through the entire duration of the city limits. However, Interstate 10, U.S. Highway 61 (a major north–south highway that links Wyoming, Minnesota, to New Orleans), and the Old Jefferson Highway (a once-major north–south highway that links Winnipeg, Canada to New Orleans) pass through the center of St. George in a north–south direction. The CDP of Old Jefferson is named for its proximity to the old Jefferson Highway.

The Capital Area Transit System (CATS) has only a limited presence in the St. George area.[98] Currently the new city has no intentions of expanding CATS' services within the new city limits.[99]

Economy

[edit]The economy of the St. George area is an integral part of the Baton Rouge economy, the East Baton Rouge Parish economy and the Baton Rouge MSA.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ JONES, TERRY L. (October 13, 2019). "Flush with election victory, St. George backers face challenges in forming new city; here's what's next". The Advocate. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "FAQ". City of St. George.

- ^ a b Rojas, Rick (October 13, 2019). "Suburbanites in Louisiana Vote to Create a New City of Their Own". The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ Map of city via GoogleMaps

- ^ a b Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broom, Lewis O. Unglesby, and M.E. Cormier vs. Chris Rials and Norman Browning, Organizers of the Petition to Incorporate St. George

- ^ http://legis.la.gov/legis/Law.aspx?d=90469 / La. Revised Statute 33:4 (Legal action contesting an incorporation)

- ^ "Judge rules against effort to create City of St. George". WBRZ. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^

- "Appeals court denies attempt to make new city of St. George for a second time". BRProud.com. July 14, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- WAFB Staff (July 14, 2023). "Appeals court denies incorporation of City of St. George". www.wafb.com. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- "Judge rules against effort to create City of St. George". WBRZ. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- Jacobs, David (July 14, 2023). "Appeals court rules against St. George incorporation". Baton Rouge Business Report. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ Nicholson, Lara (April 26, 2024). "Louisiana Supreme Court rules in favor of new City of St. George, reversing lower courts". The Advocate. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Broome v. Rials (Louisiana Supreme Court 2024), Text.

- ^ "Louisiana Indian Tribe Map". theamericanhistory.org. 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Hook, Jonathan B. (1997). The Alabama-Coushatta Indians. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-782-2.

- ^ "Acadia:Acadians:American Revolution:Acadian & French Canadian Ancestral Home". acadian-home.org. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ Bragg, Marion (1977). "Historic Names and Places on the Lower Mississippi River". Mississippi River Commission (p. 213).

- ^ "Subdivisions". data.brla.gov. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "History". stgeorgefire.com. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ "The Free State – A History and Place-Names Study of Livingston Parish". Livingston Parish American Revolution Bicentennial Committee in cooperation with the Livingston Parish Police Jury and the Louisiana American Revolution Bicentennial Commission. 1976.

- ^ BRIGHT, W. (December 1, 2003). "Native American Placenames in the Louisiana Purchase". American Speech. 78 (4): 353–362. doi:10.1215/00031283-78-4-353. ISSN 0003-1283. S2CID 145464658.

- ^ "Atchafalaya Heritage Trail Site at Highland Road Park". waterheritage.atchafalaya.org. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ "Mississippi State Name Origin". statesymbolsusa.org. September 26, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ "James W. Nicholson Hall History". lsu.edu. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "Biography Sgt. James W. Nicholson". scvruston.tripod.com. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "Ask The Advocate: About that Kress building lease; how Perkins Road got its name". The Advocate. June 9, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ "About Us". stgeorgelouisiana.com. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "One BTR". onebtr.com. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Renoud, Greg. "St. George petition fails by 71 signatures". WBRZ. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Louisiana State Legislature". legis.la.gov. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Renoud, Greg. "St. George petition fails by 71 signatures". WBRZ. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Chawla, Kiran (July 6, 2015). "Judge denies request from St. George petition organizers for re-verifying signatures on technicality". Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "FAQ's (Q: Why did the push to incorporate begin?)". stgeorgelouisiana.com. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ a b LUSSIER, CHARLES (August 24, 2019). "Why forming a new city like St. George might be easier than starting a new school system". The Advocate. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broom, Lewis O. Unglesby, and M.E. Cormier vs. Chris Rials and Norman Browning, Organizers of the Petition to Incorporate St. George" (PDF).

- ^ "Certification of the East Baton Rouge Parish Registrar of Voters regarding the Petition for Incorporation for the Proposed City of St. George" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Proclamation Number 48 JBE 2019 (Special Election – Incorporation of the City of St. George, Parish of East Baton Rouge)" (PDF).

- ^ JONES, TERRY L. (October 13, 2019). "Flush with election victory, St. George backers face challenges in forming new city; here's what's next". The Advocate. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "Proposal to incorporate St. George passes". WBRZ. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "Louisiana Revised Statute (Title 33:3. Governor's determination; special election)".

- ^ https://legis.la.gov/legis/ViewDocument.aspx?d=1182577 Act 361 of the 2020 Regular Legislative Session

- ^ http://stgeorgelouisiana.com/2020/06/19/update-gov-edwards-signs-transition-bill-into-law/ Gov. Edwards Signs St, George Transition Bill into Law

- ^ "ANNUAL OPERATING BUDGET For the Year Beginning January 1, 2023".

- ^ "2022 CA 1203 Decision Appeal" (PDF).

- ^ Duhé, Lester (July 18, 2023). "'No matter what it takes:' St. George organizers will appeal decision to La. Supreme Court, start process over if necessary". www.wafb.com. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ "Petition for Annexation Signature Page and Instructions" (PDF).

- ^ "Open Data BR". Baton Rouge Annexation History.

- ^ "Baton Rouge General Medical Center". Baton Rouge General. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Allen, Rebekah (May 16, 2014). "Metro Council approves Mall of La. annexation". The Advocate. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "St. George opposers look to annexation as possible solution". BRProud.com. October 15, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "St. George property owners begin petitions for annexation into Baton Rouge". Baton Rouge Business Report. October 18, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Lipsey's files for annexation into Baton Rouge". Baton Rouge Business Report. October 31, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ MOSBRUCKER, KRISTEN (December 3, 2019). "Turner Industries wants Baton Rouge annexation to avoid St. George; assessed property value hits $16M". The Advocate. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "First business has requested annexation into Baton Rouge and out of St. George". October 21, 2019.

- ^ "IIII United Plaza seeks annexation into Baton Rouge". Baton Rouge Business Report. October 21, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "Owners of 5 buildings worth $6.6M request Baton Rouge annexation to stay out of St. George". November 12, 2019.

- ^ "Metro Council approves first annexation requests since St. George vote". WBRZ. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- ^ Norman Browning, individually, in his capacity as Chairman of the Petition for Incorporation [of] the City of St. George and on Behalf of the electors who Signed the Incorporation Petition and Chris Rials, individually, and in his capacity as Vice-Chairman of the Petition for Incorporation of the City of St. George vs. City of Baton Rouge, and the Metropolitan Council for the City of Baton Rouge and Parish of East Baton Rouge

- ^ "St. George leaders file lawsuit to stop 'unlawful' annexation of some properties". WBRZ. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ PATERSON, BLAKE (February 11, 2020). "St. George's organizers challenge several properties' attempt to move into Baton Rouge". The Advocate. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "St. George organizers file suit to block annexations of buildings into Baton Rouge". Baton Rouge Business Report. February 11, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ https://www.legis.la.gov/legis/Law.aspx?d=88644 LA RS 33:1 - Petition for incorporation; contents; circulation; required signatures

- ^ JONES, TERRY L. (February 26, 2020). "Two more St. George-area businesses can be annexed into Baton Rouge, Metro Council rules". The Advocate. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Map". stgeorgelouisiana.com. Retrieved October 15, 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "NWS LIX – August 2016 Flood Summary Page". weather.gov. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ Agriculture, U. S. Department of (August 17, 2016), English: An aerial view taken from an MH-65 Dolphin helicopter shows severe flooding in a residential area of Baton Rouge, LA on Aug. 15, 2016. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 1st Class Melissa Leake., retrieved December 26, 2019

- ^ Gallo, Andrea (December 19, 2016). "New subdivision approved for Bayou Fountain area that flooded in August". theadvocate.com. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "Joint Statement-East Baton Rouge Flood Risk Reduction Project". Congressman Garret Graves. August 7, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ Carr; Riggs; Ingram. March 2018).pdf "CRI Final Report" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b "Active Faults in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana" (PDF).

- ^ a b Araya Eshetu Kebede (2002). "Movement along the Baton Rouge fault". Louisiana State University Master's Thesis (p. 7).

- ^ "History of Woodlawn". woodlawnhighbr.org. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Baton Rouge Fault Line V2 May 15 2017, May 15, 2017, retrieved December 27, 2019

- ^ Gallo, Andrea (June 21, 2017). "'Business as usual'? Flood-wary residents blast approval of Sanctuary development along Amite River". The Advocate. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ^ "Baton Rouge 30 x 60 Minute Geologic Quadrangle" (PDF). Louisiana Geological Survey.

- ^ "Atchafalaya Heritage Trail Site at Highland Road Park". waterheritage.atchafalaya.org. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ https://www.legis.la.gov/legis/Law.aspx?d=91316 LA RS 33:6

- ^ "Act No. 361 - Senate bill no. 423". Archived from the original on July 22, 2020.

- ^ https://www.wafb.com/2024/06/25/st-george-transition-district-elects-officers-approves-request-2-sales-tax-revenue-transfer/ WAFB - St. George Transition District elects officers, approves request for 2% sales tax revenue transfer

- ^ "BREC Park System". brec.org. 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ "Capital Area Pathways Project – Park Improvements | BREC – Parks & Recreation in East Baton Rouge Parish". www.brec.org. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "Blueways | BREC – Parks & Recreation in East Baton Rouge Parish". www.brec.org. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "LSU Hilltop Arboretum". lsu.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "Bartram Trail Conference – Louisiana". bartramtrail.org. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "Les Chenes Verts – Baton Rouge, LA – U.S. National Register of Historic Places on Waymarking.com". waymarking.com. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Guidelines for Restricting Information About Historic and Prehistoric Resources".

- ^ Survey, Historic American Buildings. "Ory House, Jean Lafitte Avenue, Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish, LA". loc.gov. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ U.S. Army Engineer District, New Orleans (July 1974). "Draft Environmental Statement: Deep Draft Access To The Ports Of New Orleans And Baton Rouge, Louisiana". U.S. Army Engineer District, New Orleans (pp. D-6–D-12).

- ^ "Warren S. Walker Plantation Home, "Woodstock," near Manchac Bayou". Louisiana Digital Library. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Capritto, Amanda (February 29, 2016). "The Story Behind Hoo Shoo Too Road's Name". 225batonrouge.com. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ Lyell D. Henry, Jr. (2016). "The Jefferson Highway: Blazing the Way from Winnipeg to New Orleans". uipress.uiowa.edu. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Advocate, CAROL ANNE BLITZERThe. "Saving a Baton Rouge family's history". Houma Today. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Morris, George (March 10, 2017). "St. George sanctuary designed to 'feel like you're in the presence of God'". theadvocate.com. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "Meet St. George Parish's new pastor, who is replacing retiring Father Mike Schatzle". theadvocate.com. March 26, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "Schools". stgeorgelouisiana.com. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ LUSSIER, CHARLES (August 24, 2019). "Why forming a new city like St. George might be easier than starting a new school system". The Advocate. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ "Petition for Incorporation" (PDF). theadvocate.com.

- ^ "A St. George school district? Here are some hurdles it would face". BRProud.com. August 29, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ "Minimum Foundation Program (MFP)". Louisiana State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education.

- ^ NICHOLSON, LARA (October 16, 2019). "How will the city of St. George work? From mayors to sewers, here are the answers". The Advocate. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ Hardy, Steve (September 18, 2018). "CATS board advances plan to shuffle routes and emphasize most popular service". theadvocate.com. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Terry L. (September 20, 2019). "Creating St. George: As early voting begins, see issues that lie ahead for potential city". theadvocate.com. Retrieved October 15, 2019.