It's All True (film)

| It's All True | |

|---|---|

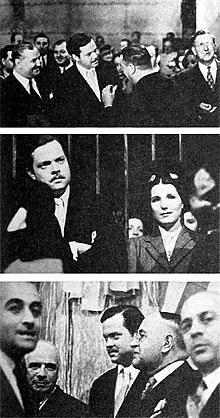

Orson Welles on location in Fortaleza, Brazil (June 26, 1942) | |

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Robert J. Flaherty (The Story of Bonito, the Bull) |

| Produced by |

|

| Cinematography |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Pictures |

| Budget | $1.2 million[1]: 73–75 |

It's All True is an unfinished Orson Welles feature film comprising three stories about Latin America. "My Friend Bonito" was supervised by Welles and directed by Norman Foster in Mexico in 1941. "Carnaval" (also known as "The Story of Samba") and "Jangadeiros" (also known as "Four Men on a Raft") were directed by Welles in Brazil in 1942. It was to have been Welles's third film for RKO Radio Pictures, after Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). The project was a co-production of RKO and the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs that was later terminated by RKO.

While some of the footage shot for It's All True was repurposed or sent to stock film libraries, approximately 200,000 feet of the Technicolor nitrate negative, most of it for the "Carnaval" episode, was dumped into the Pacific Ocean in the late 1960s or 1970s. In the 1980s a cache of nitrate negative, largely black-and-white, was found in a vault and presented to the UCLA Film and Television Archive. A 2000 inventory indicated that approximately 50,000 feet of It's All True had been preserved, with approximately 130,045 feet of the deteriorating nitrate not yet preserved.

The unrealized production was the subject of a 1993 documentary, It's All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles, written and directed by Richard Wilson, Bill Krohn and Myron Meisel.

Background

[edit]Original concept

[edit]In 1941, Orson Welles conceived It's All True as an omnibus film mixing documentary and docufiction.[2]: 221 It was to have been his third film for RKO, following Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).[3]: 109 The original sections of It's All True were "The Story of Jazz", "My Friend Bonito", "The Captain's Chair" and "Love Story". Welles registered the title of the film July 29, 1941.[4]: 365–366

"In addition to the tenuous boundary between 'real' and 'staged' events," wrote Catherine L. Benamou, "there was a thematic emphasis on the achievement of dignity by the working person, along with the celebration of cultural and ethnic diversity of North America."[3]: 109

"The Story of Jazz"

[edit]The idea for It's All True began in conversations between Welles and Duke Ellington in July 1941, the day after Welles saw Ellington's stage revue Jump for Joy in Los Angeles.[5]: 27 Welles invited Ellington to his office at RKO and told him, "I want to do the history of jazz as a picture, and we'll call it It's All True." Ellington was put under contract to score a segment with the working title, "The Story of Jazz", drawn from Louis Armstrong's 1936 autobiography, Swing That Music. "I think I wrote 28 bars, a trumpet solo by Buddy Bolden which, of course, was to be a symbol of the jazz," Ellington later recalled.[6]: 232–233 A lot of research was done and Ellington was paid up to $12,500 for his work, but Welles never heard the piece and Ellington lost track of it. "I tried to recapture some of it in A Drum Is a Woman," Ellington wrote.[7]: 240

A passionate and knowledgeable fan of traditional New Orleans jazz, Welles was part of the social network of Hollywood's Jazz Man Record Shop, a business that opened in 1939 and was instrumental in the worldwide revival of original jazz in the 1940s. Welles hired the shop's owner, David Stuart, as a researcher and consultant on the screenplay for "The Story of Jazz", which journalist Elliot Paul was put under contract to write.[8]: 42–54

The episode was to be a brief dramatization of the history of jazz performance, from its roots to its place in American culture in the 1940s. Cast as himself, Louis Armstrong would play the central role;[3]: 109 jazz pianist Hazel Scott was to portray Lil Hardin.[5]: 181 Aspects of Armstrong's biography would be interspersed with filmed performances at venues ranging from New Orleans to Chicago to New York. The work of Joe Sullivan, Kid Ory, King Oliver, Bessie Smith and others would also be spotlighted, and Ellington's original soundtrack would connect the various elements into a whole.[5]: 29

"The Story of Jazz" was to go into production in December 1941. Most of the filming would take place in the studio, but the episode also incorporated innovations including New Orleans jazz pioneer Kid Ory addressing the camera directly at an outdoor location in California, where he then lived, and animation by Oskar Fischinger.[5]: 119–120

"Both Ellington and Welles were eager to work on the project," wrote film scholar Robert Stam, "and indeed Welles's initial reluctance to go to South America derived from his reluctance to abandon the jazz project. It was only when he realized that samba was the Brazilian counterpart to jazz and that both were expressions of the African diaspora in the New World, that Welles opted for the story of carnival and the samba."[9]

In 1945, long after RKO terminated It's All True, Welles again tried to make the jazz history film, without success.[10]: 177 He spoke about it with Armstrong, who responded with a six-page autobiographical sketch.[11]: 255, 426 [12]

"Armstrong is reported to have truly regretted the eventual cancellation of the project," wrote film scholar Catherine L. Benamou.[5]: 29

"My Friend Bonito"

[edit]Mercury Productions purchased the stories for two of the segments—"My Friend Bonito" and "The Captain's Chair"—from documentary filmmaker Robert J. Flaherty in mid-1941.[5]: 33, 326 "I loved his pictures, and he wasn't getting any work, and I thought, 'Wouldn't it be nice?'" Welles told Peter Bogdanovich. "At that time I felt I was powerful and could do that."

And there was Flaherty. Instead of being a favor for him, it turned out to be a favor for me. I wanted him to direct The Captain's Chair and he didn't want to because it would have involved actors, you know, and he didn't like that. ... and then I thought of somebody else directing it. I wanted to start other people directing and all that—I thought I was beginning a great thing, you know.[4]: 156

Adapted by Norman Foster and John Fante, Flaherty's The Story of Bonito, the Bull[13]: 189 was based on an actual incident that took place in Mexico in 1908. It relates the friendship of a Mexican boy and a young bull destined to die in the ring but reprieved by the audience in Mexico City's Plaza el Toreo. "My Friend Bonito" was the only story of the original four to go into production,[3]: 109 with filming taking place in Mexico September 25 – December 18, 1941. Norman Foster directed under Welles's supervision.[5]: 311

"The Captain's Chair"

[edit]"The Captain's Chair", an unproduced segment that was also based on a Flaherty story, was originally set in the Arctic but was relocated to Hudson's Bay to conform with the premise of the film.

"Love Story"

[edit]A script for the fourth unproduced segment, "Love Story", was written by John Fante as the purportedly true story of the courtship of his immigrant parents who met in San Francisco.[14]: 9

Revised concept

[edit]

In late November 1941, Welles was appointed as a goodwill ambassador to Latin America by Nelson Rockefeller, U.S. Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs and a principal stockholder in RKO Radio Pictures.[5]: 244 The Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs was established in August 1940 by order of the U.S. Council of National Defense, and operated with funds from both the government and the private sector.[5]: 10–11 By executive order July 30, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the OCIAA within the Office for Emergency Management of the Executive Office of the President, "to provide for the development of commercial and cultural relations between the American Republics and thereby increasing the solidarity of this hemisphere and furthering the spirit of cooperation between the Americas in the interest of hemisphere defense."[15]

The mission of the OCIAA was cultural diplomacy, promoting hemispheric solidarity and countering the growing influence of the Axis powers in Latin America. The OCIAA's Motion Picture Division played an important role in documenting history and shaping opinion toward the Allied nations, particularly after the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941. To support the war effort—and for their own audience development throughout Latin America—Hollywood studios partnered with the U.S. government on a nonprofit basis, making films and incorporating Latin American stars and content into their commercial releases.[5]: 10–11

The OCIAA's Motion Picture Division was led by John Hay Whitney, who was asked by the Brazilian government to produce a documentary of the annual Rio Carnival celebration taking place in early February 1942.[5]: 40–41 In a telegram December 20, 1941, Whitney wrote Welles, "Personally believe you would make great contribution to hemisphere solidarity with this project."[1]: 65

"RKO put up the money, because they were being blackmailed, forced, influenced, persuaded—and every other word you would want to use—by Nelson Rockefeller, who was also one of its bosses then, to make this contribution to the war effort," Welles recalled some 30 years later. "I didn't want to do it, really; I just didn't know how to refuse. It was a non-paying job for the government that I did because it was put to me that it was a sort of duty."[4]: 156

Artists working in a variety of disciplines were sent to Latin America as goodwill ambassadors by the OCIAA, most on tours of two to four months. A select listing includes Misha Reznikoff and photojournalist Genevieve Naylor (October 1940–May 1943); Bing Crosby (August–October 1941); Walt Disney (August–October 1941); Aaron Copland (August–December 1941); George Balanchine and the American Ballet (1941); Rita Hayworth (1942); Grace Moore (1943); John Ford (1943) and Gregg Toland (1943). Welles was thoroughly briefed in Washington, D.C., immediately before his departure for Brazil, and film scholar Catherine L. Benamou, a specialist in Latin American affairs, finds it "not unlikely" that he was among the goodwill ambassadors who were asked to gather intelligence for the U.S. government in addition to their cultural duties. She concludes that Welles's acceptance of Whitney's request was "a logical and patently patriotic choice".[5]: 245–247

With filming of "My Friend Bonito" about two-thirds complete, Welles decided he could shift the geography of It's All True and incorporate Flaherty's story into an omnibus film about Latin America—supporting the Roosevelt administration's Good Neighbor policy, which Welles strongly advocated.[5]: 41, 246 In this revised concept, "The Story of Jazz" was replaced by the story of samba, a musical form with a comparable history and one that came to fascinate Welles. He also decided to do a ripped-from-the-headlines episode about the epic voyage of four poor Brazilian fishermen, the jangadeiros, who had become national heroes. Welles later said this was the most valuable story.[4]: 158–159 [10]: 15

"On paper and in actual practice, It's All True was programmatically designed by Welles to encourage civic unity and intercultural understanding at a time of Axis aggression, racial intolerance, and labor unrest at key sites in the hemisphere," wrote Catherine L. Benamou.[5]: 10

Apart from the requisite filming of the Rio Carnival, Welles knew only that he wanted to recreate the voyage of the jangadeiros.[10]: 15 There was no time to prepare a script: "No script was possible until Welles had actually seen the carnival," wrote Welles's executive assistant Richard Wilson. "RKO and the Coordinators Office understood this, and these were the ground rules accepted by all."[13]: 190

In return for all profits, RKO was to put up $1.2 million for the film.[1]: 65 As co-producer of the project, the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs guaranteed $300,000 against any losses RKO might incur on the release of a Class A motion picture. The project sponsors covered production expenses, travel and accommodations throughout Welles's tour. RKO paid most of these costs; the OCIAA appropriately covered the diplomatic trips associated with Welles's appointment. As an emissary of the U.S. government, Welles received no salary.[5]: 41, 328

"What's really and ironically true about It's All True," wrote associate producer Richard Wilson, "is that Welles was approached to make a non-commercial picture, then was bitterly reproached for making a non-commercial picture. Right here I'd like to make it a matter of record," Wilson continued:

Both RKO and Welles got into the project by trying to do their bit for the war effort. However: RKO, as a company responsible to stockholders, negotiated a private and tough agreement for the U.S. Government to pay it 300,000 dollars to undertake its bit. This speaks eloquently enough for its evaluation of the project as a non-commercial venture. I personally think that Orson's waiving any payment whatever for his work, and his giving up a lucrative weekly radio program, is even more eloquent. For a well-paid creative artist to work for over half a year for no remuneration is a most uncommon occurrence.[13]: 189

In addition to working on It's All True, Welles was responsible for radio programs, lectures, interviews and informal talks as part of his OCIAA-sponsored cultural mission, which was a success.[13]: 192 He spoke on topics ranging from Shakespeare to visual art to American theatre at gatherings of Brazil's elite, and his two intercontinental radio broadcasts in April 1942 were particularly intended to tell U.S. audiences that President Vargas was a partner with the Allies. Welles's ambassadorial mission would be extended to permit his travel to other nations including Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay.[5]: 247–249, 328

Welles's own expectations for the film were modest, as he told biographer Barbara Leaming:

It's All True was not going to make any cinematic history, nor was it intended to. It was intended to be a perfectly honorable execution of my job as a goodwill ambassador, bringing entertainment to the Northern Hemisphere that showed them something about the Southern one.[2]: 253

Components

[edit]"My Friend Bonito"

[edit]"Bonito the Bull", retitled "My Friend Bonito" and produced by Flaherty, was about a Mexican boy's friendship with a bull. It was filmed in Mexico in black-and-white under the direction of Norman Foster beginning in September 1941 and supervised by Welles. Because of its subject and location, the short film was later integrated into It's All True.

"Carnaval"

[edit]Two weeks after Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Welles was asked by Nelson Rockefeller (then the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs) to make a non-commercial film without salary to support the war effort as part of the Good Neighbor Policy. RKO Radio Pictures, of which Rockefeller was a major shareholder and a member of its board of directors, would foot the bill, with the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs guaranteeing up to $300,000 against potential financial losses. After agreeing to do the project, he was sent on a goodwill mission to Brazil in February 1942 to film Rio de Janeiro's Carnaval in both Technicolor and black-and-white. This was the basis for the episode also known as "The Story of Samba".

"Jangadeiros"

[edit]An article in the December 8, 1941, issue of Time, titled "Four Men on a Raft", inspired the third part of the film. It related the story of four impoverished Brazilian fishermen who set sail from Fortaleza on the São Pedro, a simple sailing raft (jangada), in September 1941. Led by Manoel Olimpio Meira (called "Jacaré"), the jangadeiros were protesting an economically exploitative system in which all fishermen were forced to give half of their catch to the jangada owners. The remaining half barely supported the men and their families. Jangadeiros also were not eligible for social security benefits accorded other Brazilians. After 61 days and 1,650 miles without any navigating instruments, braving the wind, rain and fierce sun, and making many friendly stops along the way, they sailed into Rio de Janeiro harbor as national heroes. The four men arrived in what was then the Brazilian capital to file their grievances directly to President Getúlio Vargas. The result was a bill that was signed into law by President Vargas that entitled the jangadeiros to the same benefits awarded to all union laborers—retirement funds, pensions for widows and children, housing, education and medical care.[16][a]

Filming

[edit]

Required to film the Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro in early February 1942, Welles rushed to edit The Magnificent Ambersons and finish his acting scenes in Journey into Fear. He ended his lucrative CBS radio show[13]: 189 February 2, flew to Washington, D.C., for a briefing, and then lashed together a rough cut of Ambersons in Miami with editor Robert Wise.[4]: 369–370

Welles left for Brazil on February 4 and began filming in Rio February 8, 1942.[4]: 369–370 At the time it did not seem that Welles's other film projects would be disrupted, but as film historian Catherine L. Benamou wrote, "the ambassadorial appointment would be the first in a series of turning points leading—in 'zigs' and 'zags,' rather than in a straight line—to Welles's loss of complete directorial control over both The Magnificent Ambersons and It's All True, the cancellation of his contract at RKO Radio Studio, the expulsion of his company Mercury Productions from the RKO lot, and, ultimately, the total suspension of It's All True.[5]: 46

The U.S. crew working in Brazil totalled 27,[5]: 313 supported by local artists and technicians as needed. The June 1942 issue of International Photographer gave an accounting what had been filmed to date:[18]

- Three pre-carnival celebrations in Rio and its environs

- Four nights and three days of the carnival, which required improvised lighting and sound techniques that proved a great success

- Every conceivable scenic attraction in the city and surrounding hills and mountains

- Test footage of the fishermen in Fortaleza

- A three-day Easter ceremony at Ouro Preto

- Every samba nightclub in Rio, with most of the scenes rehearsed and staged

- The reenactment of the arrival of the jangadeiros in Rio harbor

- Two weeks of closeups and orchestra recordings made at the Cinédia studio, which Welles had rented[18]

"A part of this time the crew has worked day and night," the magazine reported, "recording in the afternoons and shooting after dinner."[18] Actors and performers in the "Carnaval" segment included Grande Otelo, Odete Amaral, Linda Batista, Emilinha Borba, Chucho Martínez Gil, Moraes Netto and Pery Ribeiro.[5]: 313

Filming the reenactment of the epic voyage of the four jangadeiros cost the life of their leader. On May 19, 1942, while Welles and the crew were preparing to film the arrival of the São Pedro, a launch towing the jangada turned sharply and severed the line. The raft overturned and all four men were cast into the ocean. Only three were rescued; Jacaré disappeared while trying to swim to shore. Welles resolved to finish the episode as a tribute to Jacaré. For continuity, Jacaré's brother stood in as Jacaré, and the narrative was modified to focus on a young fisherman who dies at sea shortly after his marriage to a beautiful young girl (Francisca Moreira da Silva). His death becomes the catalyst for the four jangadeiros' voyage of protest. Shot in Technicolor before the accident, the entry into Rio harbor includes Jacaré, presenting an opportunity for Welles to pay him homage in the closing narration.[5]: 52–55

Filming in Rio concluded June 8, 1942,[5]: 315 and continued in southeastern Brazil until July 24.[5]: 317

Termination of the project

[edit]In 1942 RKO Pictures underwent major changes under new management. Nelson Rockefeller, the primary backer of the Brazil project, left its board of directors, and Welles's principal sponsor at RKO, studio president George Schaefer, resigned. RKO took control of Ambersons and edited the film into what the studio considered a commercial format. Welles's attempts to protect his version ultimately failed.[19][20] In South America, Welles requested resources to finish It's All True. Given a limited amount of black-and-white film stock and a silent camera, he was able to finish shooting the episode about the jangadeiros, but RKO refused to support further production on the film.

"It was a tax write off, so they lost nothing," Welles later said. "Otherwise they would have been struggling to get something out of it. However bad, they could have made a bad musical out of just the nightclub footage. They would have got a return on their money. But they didn't want a return on their money. It was better for them to drop it in the sea, which is what they did."[2]: 256

Welles returned to the United States August 22, 1942, after more than six months in South America.[4]: 372 He sought to continue the project elsewhere and tried to persuade other movie studios to finance the completion of It's All True. Welles eventually managed to purchase some of the footage of the film, but ended up relinquishing ownership back to RKO based on his inability to pay the storage costs of the film.

Welles thought that the film had been cursed. Speaking about the production in the second episode of his 1955 BBC-TV series Orson Welles' Sketch Book, Welles said that a voodoo doctor who had been preparing a ceremony for It's All True was deeply offended at the film being terminated. Welles found his script pierced completely through with a long needle. "And to the needle was attached a length of red wool. This was the mark of the voodoo," Welles said. "And the end of that story is that it was the end of the film. We were never allowed to finish it."[21][22][b]

Repurposing

[edit]Footage from It's All True was used in RKO films including The Falcon in Mexico (1944)[23]: 349 and, reportedly, the musical showcase Pan-Americana (1945). Some black-and-white film from the "Carnaval" sequence was sold as stock footage for The March of Time,[5]: 281, 361 [24][25] a newsreel series with a long association with RKO.[26]: 110, 281

An independently produced film released in 1947 by United Artists, New Orleans, has its basis in It's All True. Elliot Paul, who had been under contract to Welles to write "The Story of Jazz" segment, is credited as screenwriter for the film, an all-star history of jazz starring Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday.[27]: 138–139 In December 1946 Welles's assistant Richard Wilson wrote an attorney to note the similarity between the story of New Orleans and the concept of "The Story of Jazz".[5]: 361

In 1956, RKO released The Brave One, a film about the friendship between a young Mexican boy and a bull who is destined to die in the bullring but is spared by the crowd. Much controversy surrounded the film when its screenwriter, "Robert Rich", received an Academy Award for Best Story. Orson Welles later said, "Dalton Trumbo wrote it under a pseudonym; he couldn't take credit because he was a victim of the blacklist."

So nobody came up to get the Oscar, and everybody said, "What a shame—poor Dalton Trumbo, victim of McCarthyism." But, in fact, the story was not his or mine but Robert Flaherty's. The King brothers were with RKO, and they got the rights for it—and Trumbo took a great big invisible bow. Which Flaherty deserved.[4]: 155

"The Brave One illustrates the extent to which plagiarism could become a modus operandi for low-budget studio film production," wrote film scholar Catherine L. Benamou, "legitimated by the studios' legal ownership of script material and footage, and euphemized as the productive recycling of outdated or abandoned projects."[5]: 282

Benamou also cites similarities between a script Welles wrote after returning to the United States, when he hoped to salvage some of the "Carnaval" footage, and another RKO film. "There is a notable resonance between the later version of the 'Michael Guard' script and the basic plot and setting of the high-budget Notorious, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and released with considerable success by RKO in 1946," Benamou wrote. The plot involves two European Americans in Brazil, one of them a woman spy who discovers a clandestine Nazi operation. Finding it plausible that the Welles script may have been used, Benamou called for further research.[5]: 283, 361

Recovery

[edit]A 1952 inventory documented that the RKO vault contained the following footage from It's All True:

- Black-and-white negative equal to 21 reels of footage of "My Friend Bonito"

- Negative matching 15 reels of "Jangadeiros"

- Seven reels of black-and-white film and one reel of color film for the "Carnaval" segment

- Uncut Technicolor negative (200,000 feet) and music sound negative (50,000 feet) shot for "Carnaval"[5]: 277

In 1953, however, It's All True cinematographer George Fanto was told by RKO that no one knew what had become of the footage. Fanto wished to locate the film after finding someone to finance its completion.[5]: 277

The film remained in the vault when RKO was acquired by Desilu Productions in December 1957. Desi Arnaz recalled that in his negotiations with RKO's Dan O'Shea, "I had asked him for all the stock footage to be thrown into the deal. I knew there was about a million feet of film Orson Welles had shot in Brazil which had never been seen."[28]: 293 The American Film Institute later became interested in locating the footage after learning that Arnaz, a good friend of Welles, had made inquiries in the mid-1960s about printing some of the negative.[5]: 277–278

In 1967 the footage came under the control of Paramount Pictures, and some elements—the Technicolor sequence from "Four Men on a Raft", parts of "Carnaval" and scenes from "My Friend Bonito"—were incorporated into Paramount's stock film library. In the late 1960s or 1970s, perhaps fearing legal action by Grande Otelo—then a celebrity, but an unknown at the time he was filmed for It's All True—Paramount discarded some 200,000 feet of Technicolor nitrate negative into the Pacific Ocean.[5]: 277–279

In 1981 Fred Chandler, Paramount's director of technical services, was looking for storage space in the studio's Hollywood vault when he happened across the long-forgotten footage from It's All True. He found 250 metal film cans labeled "Bonito" and "Brazil", each holding held eight to ten rolls of black-and-white nitrate negative.[29] Seeing a few shots of the "Jangadeiros" sequence, Chandler recognized it immediately. Orson Welles was told of the discovery but he refused to look at it. "He told me the film was cursed," said Chandler, who donated the film to the American Film Institute. Chandler raised $110,000 to fund the creation of a short documentary film—It's All True: Four Men on a Raft (1986)—using some of the footage.[30] The total recovery came to 309 cans of black-and-white nitrate negative and five cans of unidentified positive film. The AFI presented the material to the UCLA Film and Television Archive.[5]: 278

In May 1982, approximately 47 seconds of footage from It's All True was broadcast on the BBC-TV series Arena, in a documentary titled The Orson Welles Story. "It's a tiny roll of disconnected Technicolor shots," producer-narrator Leslie Megahey says as the silent film is presented. "We found this roll with the help of an archivist at RKO in a Hollywood film library, labelled as stock footage of the Carnival. Welles himself has probably never seen it."[31]

The six-part 1987 BBC-TV series, The RKO Story, devoted its fourth episode—titled "It's All True"—to Orson Welles's time at RKO. The last 20 minutes of the hour-long episode recount the troubled production of It's All True. Music, sound effects and an excerpt from the first episode of Welles's subsequent CBS Radio series, Hello Americans, were added to the silent recovered footage, nearly all from the "Carnaval" episode.[32][33][c]

Preservation status

[edit]In her book, It's All True: Orson Welles's Pan-American Odyssey (2007), Catherine L. Benamou presents an inventory of the surviving It's All True footage stored in the UCLA Film and Television Archive nitrate vaults. These materials were present in a June 2000 inventory.

- "My Friend Bonito" — Approximately 67,145 feet of black-and-white not preserved; 8,000 feet preserved.[5]: 312

- "Carnaval" — Approximately 32,200 feet of black-and-white not preserved; 3,300 feet preserved. Approximately 2,700 feet of Technicolor not preserved (in Paramount Studios vaults); approximately 2,750 feet processed for use in the 1993 documentary.[5]: 315

- "Jangadeiros" — Approximately 28,000 feet of black-and-white not preserved; approximately 35,950 feet preserved.[5]: 317

On June 16, 2023, Benamou revealed on Twitter that Paramount Pictures was scanning the remaining footage at the UCLA Film and Television Archive for preservation. [35]

Reconstructions

[edit]It's All True: Four Men on a Raft

[edit]It's All True: Four Men on a Raft is a short documentary film released in 1986.

The preservation of It's All True at UCLA was supported by the American Film Institute, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the initiative of Fred Chandler and Welles's executive assistant Richard Wilson.[5]: 278 Wilson had worked with Welles since 1937—in theatre, radio and film.[36] As Welles's executive assistant on It's All True, Wilson was with the first group to arrive in Brazil, on January 27, 1942, two weeks before Welles himself.[23]: 336

When Welles declined to look at the newly recovered footage, Wilson accepted the difficult task of making sense of it. After he spent days scrutinizing the unprinted negative Wilson identified about seven hours of the "Jangedeiros" footage shot at Fortaleza. He edited some of the film into a coherent ten-minute sequence, which was used in a short film that was titled It's All True: Four Men on a Raft. The other 12 minutes of the film included the on-screen recollections of Wilson and cinematographer George Fanto.[30]

The resulting 22-minute documentary short made its debut at the Venice Film Festival August 30, 1986. The short film was created to help raise funds for the preservation and transfer of the film from nitrate to safety stock[29]—a process that is still far from complete.[5]: 312, 315, 317

It's All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles

[edit]It's All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles is a 1993 documentary feature narrated by Miguel Ferrer.[37] The driving force behind the film was Richard Wilson, who collaborated with Welles on It's All True and most of his stage productions, radio shows, and other feature films. In 1986 Wilson, along with Bill Krohn, the Los Angeles correspondent for Cahiers du cinéma, made a 22-minute trailer to raise money for the project. They were joined by film critic Myron Meisel the next year and Catherine Benamou in 1988. Benamou, a Latin American and Caribbean specialist fluent in the dialect spoken by the jangadeiros, performed the field research and conducted interviews with the film's original participants in Mexico and Brazil. Wilson would continue to work despite having been diagnosed with cancer which he only disclosed to family and close friends. It wasn't until after his death in 1991 when the project finally got the funding needed to complete the documentary from Canal Plus.

In 1993, New York Times film critic Vincent Canby called the documentary "a must see ... a long, seductive footnote to a cinema legend".[37] It was named the year's Best Non-Fiction Film by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and its filmmakers received a special citation from the National Society of Film Critics.[36]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In 1984, Welles narrated a documentary series created by Neil Hollander, The Last Sailors: The Final Days of Working Sail, that includes a 12-minute segment on the jangadeiros of northern Brazil. The segment ends with three sails on the horizon: "The world of the jangadeiros. Elemental, unique, shrinking. A world whose end is in sight."[17]

- ^ That scene from Orson Welles' Sketch Book introduces the 1993 documentary, It's All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles.

- ^ Contrary to what is stated in the BBC-TV documentary The RKO Story, Welles did not make regular broadcasts from Brazil for CBS Radio. The audio in the documentary beginning 44:48 is from the first episode of Welles's OCIAA-sponsored radio series, Hello Americans, broadcast live November 15, 1942, from CBS studios in Los Angeles.[34]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c McBride, Joseph, What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2006, ISBN 0-8131-2410-7

- ^ a b c Leaming, Barbara, Orson Welles, A Biography. New York: Viking, 1985 ISBN 0-670-52895-1

- ^ a b c d Benamou, Catherine, "It's All True". Barnard, Tim, and Peter Rist (eds.), South American Cinema: A Critical Filmography, 1915-1994. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998 ISBN 978-0-292-70871-6

- ^ a b c d e f g h Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers 1992 ISBN 0-06-016616-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj Benamou, Catherine L., It's All True: Orson Welles's Pan-American Odyssey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-520-24247-0

- ^ Teachout, Terry, Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington. New York: Gotham Books, 2013 ISBN 978-1-592-40749-1

- ^ Ellington, Duke, Music Is My Mistress. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1968; Da Capo Press, 1973. ISBN 0306800330

- ^ Ginell, Cary, Hot Jazz for Sale: Hollywood's Jazz Man Record Shop. Lulu.com: Cary Ginell, 2010 ISBN 978-0-557-35146-6

- ^ Stam, Robert, "Orson Welles, Brazil, and the Power of Blackness". Simon, William G. (ed.), Persistence of Vision: The Journal of the Film Faculty of The City University of New York, Special Issue on Orson Welles, Number 7, 1989, page 107.

- ^ a b c Wood, Bret, Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1990 ISBN 0-313-26538-0

- ^ Teachout, Terry, Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2009 ISBN 978-015-101089-9

- ^ Wood, Bret, "The Road to New Orleans" (supplementary essay), New Orleans, Archived 2014-03-25 at the Wayback Machine Kino Lorber Home Video, Region 1 DVD, April 25, 2000

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, Richard, "It's Not Quite All True". Sight & Sound, Volume 39 Number 4, Autumn 1970.

- ^ Callow, Simon, Orson Welles: Hello Americans. New York: Viking, 2006 ISBN 0-670-87256-3

- ^ Roosevelt, Franklin D., "Executive Order 8840 Establishing the Office of Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs", July 30, 1941. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, University of California, Santa Barbara

- ^ "Four Men on a Raft". Time. Vol. 38, no. 23. December 8, 1941. p. 30. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Mertes, Neil, and Hollander, Harald, The Last Sailors: The Final Days of Working Sail (1984). Adventure Film Productions, Transdisc Music, S.L., 2006. Region 2 DVD, disc 2, 12:30–24:50

- ^ a b c "With Welles in Rio". International Photographer. June 1942. p. 28.

- ^ "The Magnificent Ambersons". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Barnett, Vincent L. "Cutting Koerners: Floyd Odlum, the Atlas Corporation and the Dismissal of Orson Welles from RKO". Film History: An International Journal, Volume 22, Number 2, 2010, pp.182–198.

- ^ "Orson Welles Sketch Book Transcripts, Episode 2". Wellesnet. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ "Orson Welles Sketch Book Episode 2: Critics". YouTube. 21 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ a b Brady, Frank, Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1989 ISBN 0-385-26759-2

- ^ "Brazil". "South American Front 1944" (The March of Time, Vol. 10, Ep. 8), a March 1944 newsreel released as 1945 U.S. Army educational film EF-105, at the Internet Archive (1:44–2:27). Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ^ "Synopsis, The March of Time Newsreels" (PDF). HBO Archives. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ^ Fielding, Raymond, The March of Time, 1935–1951. New York: Oxford University Press 1978 hardcover ISBN 0-19-502212-2

- ^ Stowe, David Ware, Swing Changes: Big-Band Jazz in New Deal America. Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.]: Harvard University Press, 1998, ISBN 9780674858268

- ^ Arnaz, Desi. A Book. New York: William Morrow, 1976. ISBN 0688003427

- ^ a b Kehr, Dave (September 14, 1986). "A Welles Spring". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Farber, Stephen (August 28, 1986). "1942 Welles Film Footage Recovered". The New York Times. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Arena—The Orson Welles Story BBC, 1982. Technicolor footage from "Carnaval" and "Jangadeiros" episodes 54:52–55:39. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ The RKO Story—"It's All True" BBC, 1987. Discussion of It's All True, including Technicolor and black-and-white footage from the film, begins 38:10.

- ^ "It's All True". Hollywood, The Golden Years: The RKO Story, Episode 4. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ^ Hello Americans, episode 1. Internet Archive. Event occurs at 4:19. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- ^ wellesnet (2023-06-17). "Paramount scanning remaining 'It's All True' footage". Wellesnet | Orson Welles Web Resource. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ a b "Richard Wilson–Orson Welles Papers 1930–2000". Special Collections Library, University of Michigan. Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- ^ a b "Movie Review: It's All True Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles (1993)". Canby, Vincent, The New York Times, October 15, 1993. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Truth and Consequences," Chicago Reader, October 29, 1993

External links

[edit]- It's All True at IMDb

- "Life Goes to Rio Party; Orson Welles frolics at famous Mardi Gras". Life, May 18, 1942, pp. 99–101

- Orson Welles filming at Urca Casino (April 1942), b+w, silent, 2:33 (stock footage)

- Orson Welles in Brazil University of Michigan Special Collections Library (Flickr)

- "Brazil" at the Internet Archive — a 1945 U.S. Army educational film presenting The March of Time episode, "South American Front 1944" (March 1944), which utilizes Carnaval footage shot for It's All True at the beginning (1:44–2:27) of its review of the strategic significance of Brazil in World War II

- Orson Welles and the Hollywood System — program about It's All True at the UCLA Film and Television Archive (August 10, 2006)

- 1942 films

- Brazilian documentary films

- RKO Pictures films

- Films set in Rio de Janeiro (city)

- Films set in Brazil

- Films set in Mexico

- American documentary films

- American anthology films

- Films directed by Norman Foster

- Films directed by Orson Welles

- Samba

- Films with screenplays by Orson Welles

- 1940s unfinished films

- 1942 documentary films

- 1940s American films