Edward Said

Edward Said | |

|---|---|

Said in Seville, Spain, 2002 | |

| Born | Edward Wadie Said 1 November 1935 |

| Died | 24 September 2003 (aged 67) New York City, U.S. |

| Burial place | Protestant Cemetery, Brummana, Lebanon |

| Citizenship | American |

| Education | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2, including Najla |

| Relatives |

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

Notable ideas | |

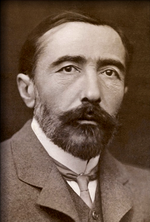

Edward Wadie Said[a] (1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American academic, literary critic, and political activist.[1] As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he was among the founders of post-colonial studies.[2] As a cultural critic, Said is best known for his book Orientalism (1978), a foundational text which critiques the cultural representations that are the bases of Orientalism—how the Western world perceives the Orient.[3][4][5][6] His model of textual analysis transformed the academic discourse of researchers in literary theory, literary criticism, and Middle Eastern studies.[7][8][9][10]

Born in Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine, in 1935, Said was a United States citizen by way of his father, who had served in the United States Army during World War I. After the 1948 Palestine war, he relocated the family to Egypt, where they had previously lived, and then to the United States. Said enrolled at the secondary school Victoria College while in Egypt and Northfield Mount Hermon School after arriving in the United States. He graduated with a BA in English from Princeton University in 1957, and later with an MA (1960) and a PhD (1964) in English Literature from Harvard University.[1] His principal influences were Antonio Gramsci, Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Michel Foucault, and Theodor W. Adorno.[10]

In 1963, Said joined Columbia University as a member of the English and Comparative Literature faculties, where he taught and worked until 2003. He lectured at more than 200 other universities in North America, Europe, and the Middle East.[11]

As a public intellectual, Said was a member of the Palestinian National Council supporting a two-state solution that incorporated the Palestinian right of return, before resigning in 1993 due to his criticism of the Oslo Accords.[12][13] He advocated for the establishment of a Palestinian state to ensure political and humanitarian equality in the Israeli-occupied territories, where Palestinians have witnessed the increased expansion of Israeli settlements. However, in 1999, he argued that sustainable peace was only possible with one Israeli–Palestinian state.[14] He defined his oppositional relation with the Israeli status quo as the remit of the public intellectual who has "to sift, to judge, to criticize, to choose, so that choice and agency return to the individual".

In 1999, Said and Argentine-Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim co-founded the West–Eastern Divan Orchestra, which is based in Seville, Spain. Said was also an accomplished pianist, and, with Barenboim, co-authored the book Parallels and Paradoxes: Explorations in Music and Society (2002), a compilation of their conversations and public discussions about music at Carnegie Hall in New York City.[15]

Life and career

Early life

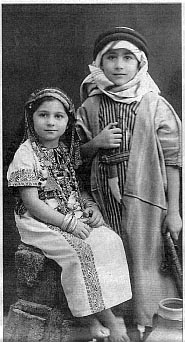

Said was born on 1 November 1935[16] into a family of Palestinian Christians in the city of Jerusalem, at the time under the British Mandate for Palestine.[17] His parents were born in the Ottoman Empire: his mother Hilda Said (née Musa) was half Palestinian and half Lebanese, and was raised in the city of Nazareth; and his father Wadie "William" Said was a Jerusalem-based Palestinian businessman.[18][19] Both Hilda and Wadie were Arab Christians, adhering to Protestantism.[20][21] During World War I, Wadie served in the American Expeditionary Forces, subsequently earning United States citizenship for himself and his immediate family.[22][23][24]

In 1919, Wadie and his cousin established a stationery business in Cairo, Egypt.[19]: 11

Although he was raised Protestant, Said became an agnostic in his later years.[25][26][27][28][29]

Education

Said's childhood was split between Jerusalem and Cairo: he was enrolled in Jerusalem's St. George's School, a British boys' school run by the local Anglican Diocese, but stopped going to his classes when growing intercommunal violence between Palestinian Arabs and Palestinian Jews made it too dangerous for him to continue attending, prompting his family to leave Jerusalem at the onset of the 1947–1949 Palestine War.[30] By the late 1940s, Said was in Alexandria, enrolled at the Egyptian branch of Victoria College, where "classmates included Hussein of Jordan, and the Egyptian, Syrian, Jordanian, and Saudi Arabian boys whose academic careers would progress to their becoming ministers, prime ministers, and leading businessmen in their respective countries."[19]: 201 However, he was expelled in 1951 for troublesome behaviour, though his academic performance was high. Having relocated to the United States, Said attended Northfield Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts—a socially élite, college-prep boarding school where he struggled with social alienation for a year. Nonetheless, he continued to excel academically and achieved the rank of either first (valedictorian) or second (salutatorian) out of a class of 160 students.[31]

In retrospect, he viewed being sent far from the Middle East as a parental decision much influenced by "the prospects of deracinated people, like us the Palestinians, being so uncertain that it would be best to send me as far away as possible."[31] The realities of peripatetic life—of interwoven cultures, of feeling out of place, and of homesickness—so affected the schoolboy Edward that themes of dissonance feature in the work and worldview of the academic Said.[31] At school's end, he had become Edward W. Said—a polyglot intellectual (fluent in English, French, and Arabic). He graduated with an A.B. in English from Princeton University in 1957 after completing a senior thesis titled "The Moral Vision: André Gide and Graham Greene."[32] He later received Master of Arts (1960) and Doctor of Philosophy (1964) degrees in English Literature from Harvard University.[19]: 82–83 [1]

Career

In 1963, Said joined Columbia University as a member of the English and Comparative Literature faculties, where he taught and worked until 2003. In 1974, he was Visiting Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard; during the 1975–76 period, he was a Fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Science, at Stanford University. In 1977, he became the Parr Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, and subsequently was the Old Dominion Foundation Professor in the Humanities; and in 1979 was Visiting Professor of Humanities at Johns Hopkins University.[33]

Said also worked as a visiting professor at Yale University, and lectured at more than 200 other universities in North America, Europe, and the Middle East.[11][34] Editorially, Said served as president of the Modern Language Association, as editor of the Arab Studies Quarterly in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, on the executive board of International PEN, and was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Royal Society of Literature, the Council of Foreign Relations,[33] and the American Philosophical Society.[35] In 1993, Said presented the BBC's annual Reith Lectures, a six-lecture series titled Representation of the Intellectual, wherein he examined the role of the public intellectual in contemporary society, which the BBC published in 2011.[36]

In his work, Said frequently researches the term and concept of the cultural archive, especially in his book Culture and Imperialism (1993). He states the cultural archive is a major site where investments in imperial conquest are developed, and that these archives include "narratives, histories, and travel tales."[37] Said emphasizes the role of the Western imperial project in the disruption of cultural archives, and theorizes that disciplines such as comparative literature, English, and anthropology can be directly linked to the concept of empire.

Literary productions

Said's first published book, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (1966), was an expansion of the doctoral dissertation he presented to earn the PhD degree. Abdirahman Hussein said in Edward Saïd: Criticism and Society (2010), that Conrad's novella Heart of Darkness (1899) was "foundational to Said's entire career and project".[38][39] In Beginnings: Intention and Method (1974), Said analyzed the theoretical bases of literary criticism by drawing on the insights of Vico, Valéry, Nietzsche, de Saussure, Lévi-Strauss, Husserl, and Foucault.[40] Said's later works included

- The World, the Text, and the Critic (1983),

- Nationalism, Colonialism, and Literature: Yeats and Decolonization (1988),

- Culture and Imperialism (1993),

- Representations of the Intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures (1994),

- Humanism and Democratic Criticism (2004), and

- On Late Style (2006).

Orientalism

Said became an established cultural critic with the book Orientalism (1978), a critique of Orientalism as the source of the false cultural representations in western-eastern relations. The thesis of Orientalism proposes the existence of a "subtle and persistent Eurocentric prejudice against Arabo–Islamic peoples and their culture",[41] which originates from Western culture's long tradition of false, romanticized images of Asia, in general, and the Middle East in particular. Said wrote that such cultural representations have served as implicit justifications for the colonial and imperial ambitions of the European powers and of the U.S. Likewise, Said denounced the political and the cultural malpractices of the régimes of the ruling Arab élites who he felt internalized the false and romanticized representations of Arabic culture that were created by Anglo–American Orientalists.[41]

Orientalism proposed that much Western study of Islamic civilization was political intellectualism, meant for the self-affirmation of European identity, rather than objective academic study; thus, the academic field of Oriental studies functioned as a practical method of cultural discrimination and imperialist domination—that is to say, the Western Orientalist knows more about "the Orient" than do "the Orientals."[41][42]: 12

Western Art, Orientalism continues, has misrepresented the Orient with stereotypes since Antiquity, as in the tragedy The Persians (472 BCE), by Aeschylus, where the Greek protagonist falls because he misperceived the true nature of The Orient.[42]: 56–57 The European political domination of Asia has biased even the most outwardly objective Western texts about The Orient, to a degree unrecognized by the Western scholars who appropriated for themselves the production of cultural knowledge—the academic work of studying, exploring, and interpreting the languages, histories, and peoples of Asia. Therefore, Orientalist scholarship implies that the colonial subaltern (the colonised people) were incapable of thinking, acting, or speaking for themselves, thus are incapable of writing their own national histories. In such imperial circumstances, the Orientalist scholars of the West wrote the history of the Orient—and so constructed the modern, cultural identities of Asia—from the perspective that the West is the cultural standard to emulate, the norm from which the "exotic and inscrutable" Orientals deviate.[42]: 38–41

Criticism of Orientalism

Orientalism provoked much professional and personal criticism for Said among academics.[43] Traditional Orientalists, such as Albert Hourani, Robert Graham Irwin, Nikki Keddie, Bernard Lewis, and Kanan Makiya, suffered negative consequences, because Orientalism affected public perception of their intellectual integrity and the quality of their Orientalist scholarship.[44][45][47] The historian Keddie said that Said's critical work about the field of Orientalism had caused, in their academic disciplines:

Some unfortunate consequences ... I think that there has been a tendency in the Middle East [studies] field to adopt the word Orientalism as a generalized swear-word, essentially referring to people who take the "wrong" position on the Arab–Israeli dispute, or to people who are judged "too conservative." It has nothing to do with whether they are good or not good in their disciplines. So, Orientalism, for many people, is a word that substitutes for thought, and enables people to dismiss certain scholars and their works. I think that is too bad. It may not have been what Edward Saïd meant, at all, but the term has become a kind of slogan.

— Approaches to the History of the Middle East (1994), pp. 144–45.[48]

In Orientalism, Said described Bernard Lewis, the Anglo–American Orientalist, as "a perfect exemplification [of an] Establishment Orientalist [whose work] purports to be objective, liberal scholarship, but is, in reality, very close to being propaganda against his subject material."[42]: 315

Lewis responded with a harsh critique of Orientalism accusing Said of politicizing the scientific study of the Middle East (and Arabic studies in particular); neglecting to critique the scholarly findings of the Orientalists; and giving "free rein" to his biases.[49]

Said retorted that in The Muslim Discovery of Europe (1982), Lewis responded to his thesis with the claim that the Western quest for knowledge about other societies was unique in its display of disinterested curiosity, which Muslims did not reciprocate towards Europe. Lewis was saying that "knowledge about Europe [was] the only acceptable criterion for true knowledge." The appearance of academic impartiality was part of Lewis's role as an academic authority for zealous "anti–Islamic, anti–Arab, Zionist, and Cold War crusades."[42]: 315 [50] Moreover, in the Afterword to the 1995 edition of the book, Said replied to Lewis's criticisms of the first edition of Orientalism (1978).[50][42]: 329–54

Influence of Orientalism

In the academy, Orientalism became a foundational text of the field of post-colonial studies, for what the British intellectual Terry Eagleton said is the book's "central truth ... that demeaning images of the East, and imperialist incursions into its terrain, have historically gone hand in hand."[51]

Both Said's supporters and his critics acknowledge the transformative influence of Orientalism upon scholarship in the humanities; critics say that the thesis is an intellectually limiting influence upon scholars, whilst supporters say that the thesis is intellectually liberating.[52][53] The fields of post-colonial and cultural studies attempt to explain the "post-colonial world, its peoples, and their discontents",[2][54] for which the techniques of investigation and efficacy in Orientalism, proved especially applicable in Middle Eastern studies.[7]

As such, the investigation and analysis Said applied in Orientalism proved especially practical in literary criticism and cultural studies,[7] such as the post-colonial histories of India by Gyan Prakash,[55] Nicholas Dirks[56] and Ronald Inden,[57] modern Cambodia by Simon Springer,[58] and the literary theories of Homi K. Bhabha,[59] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak[60] and Hamid Dabashi (Iran: A People Interrupted, 2007).

In Eastern Europe, Milica Bakić–Hayden developed the concept of Nesting Orientalisms (1992), derived from the ideas of the historian Larry Wolff (Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment, 1994) and Said's ideas in Orientalism (1978).[61] The Bulgarian historian Maria Todorova (Imagining the Balkans, 1997) presented the ethnologic concept of Nesting Balkanisms (Ethnologia Balkanica, 1997), which is derived from Milica Bakić–Hayden's concept of Nesting Orientalisms.[62]

In The Impact of "Biblical Orientalism" in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (2014), the historian Lorenzo Kamel, presented the concept of "Biblical Orientalism" with an historical analysis of the simplifications of the complex, local Palestinian reality, which occurred from the 1830s until the early 20th century.[63] Kamel said that the selective usage and simplification of religion, in approaching the place known as "The Holy Land", created a view that, as a place, the Holy Land has no human history other than as the place where Bible stories occurred, rather than as Palestine, a country inhabited by many peoples.

The post-colonial discourse presented in Orientalism, also influenced post-colonial theology and post-colonial biblical criticism, by which method the analytical reader approaches a scripture from the perspective of a colonial reader.[64] Another book in this area is Postcolonial Theory (1998), by Leela Gandhi, explains Post-colonialism in terms of how it can be applied to the wider philosophical and intellectual context of history.[65]

Political activities

Arab–Israeli conflict

In 1967, consequent to the Six-Day War, Said became a public intellectual when he acted politically to counter the stereotyped misrepresentations (factual, historical, cultural) with which American news media explained the Arab–Israeli conflict; reportage divorced from the historical realities of the Middle East, in general, and from Israel and the Palestinian territories, in particular. To address, explain, and correct such perceived orientalism, Said published The Arab Portrayed (1968), a descriptive essay about images of "the Arab" that are meant to evade specific discussion of the historical and cultural realities of the peoples represented in the Middle East, featured in journalism (print, photograph, television) and some types of scholarship (specialist journals).[66]

Views on Zionism

In the essay "Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims" (1979), Said argued in favour of the political legitimacy and philosophical authenticity of the claims and right to a Jewish homeland, while also asserting the simultaneously inherent right of national self-determination for the Palestinian people.[67] He also characterized Israel's founding as it happened, the displacement of the Palestinian Arabs that accompanied it, and the subjugation of the Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied territories as a manifestation of Western-style imperialism. His books on this topic include The Question of Palestine (1979), The Politics of Dispossession (1994), and The End of the Peace Process (2000).

During a lecture conference at the University of Washington in 2003, Said affirmed that Israeli Jews had grounds for a territorial claim to Palestine (or the Land of Israel), but maintained that it was not "the only claim or the main claim" vis-à-vis all of the other ethnic groups (including Jews and Arabs) who have inhabited the region throughout human history:

Halleran: "Professor Said, do the Zionists have any historical claim to the lands of Israel?"

Said: "Of course! But I would not say that the Jewish claim, or the Zionist claim, is the only claim or the main claim; I say that it is a claim among many others. Certainly, the Arabs have a much greater claim because they have had a longer history of inhabitance—of actual residence in Palestine—than the Jews did. If you look at the history of Palestine, there's been some quite interesting work done by biblical archaeologists... you'll see that the period of actual Israelite—as it was called in the Old Testament—dominance in Palestine amounts to about 200 to 250 years. But there were Moabites, there were Jebusites, there were Canaanites, there were Philistines, there were many other people in Palestine at the time and before and after. And to isolate one of them and say, 'That's the real owner of the land,' I mean, that is—that is fundamentalism. Because the only way you can back it up is say, 'Well, God gave it to us.' [...] So, I think the people who have a history of residence in Palestine for a certain amount of time—including Jews, yes, and, of course, the Arabs—have a claim. But... this is very important: I don't think any claim [...] nobody has a claim that overrides all the others and entitles that person with that so-called claim to drive people out!"— "Imperial Continuity – Palestine, Iraq, and U.S. Policy"[68] (8 May 2003)

Said's argument against the Religious Zionism traditionally espoused by Jewish fundamentalists (i.e., citing God to project the Jewish/Israeli claim as superior to the Arab/Palestinian claim) asserted that such justifications were inherently irrational because they would, among other factors, enable Christians and Muslims of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds to lay superseding territorial claims to Palestine on the basis of their faith.

Palestinian National Council

From 1977 until 1991, Said was an independent member of the Palestinian National Council (PNC).[69] In 1988, he was a proponent of the two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and voted for the establishment of the State of Palestine at a meeting of the PNC in Algiers. In 1993, Said quit his membership in the Palestinian National Council, to protest the internal politics that led to the signing of the Oslo Accords (Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, 1993), which he thought had unacceptable terms, and because the terms had been rejected by the Madrid Conference of 1991.

Said disliked the Oslo Accords for not producing an independent State of Palestine, and because they were politically inferior to a plan that Yasir Arafat had rejected—a plan Said had presented to Arafat on behalf of the U.S. government in the late 1970s.[70] Especially troublesome to Said was his belief that Yasir Arafat had betrayed the right of return of the Palestinian refugees to their houses and properties in the Green Line territories of pre-1967 Israel, and that Arafat ignored the growing political threat of the Israeli settlements in the occupied territories that had been established since the conquest of Palestine in 1967.

In 1995, in response to Said's political criticisms, the Palestinian Authority (PA) banned the sale of Said's books;[71] however, the PA lifted the book ban when Said publicly praised Yasir Arafat for rejecting Prime Minister Ehud Barak's offers at the Middle East Peace Summit at Camp David (2000) in the U.S.[72][73]

In the mid-1990s, Said wrote the foreword to the history book Jewish History, Jewish Religion: The Weight of Three Thousand Years (1994), by Israel Shahak, about Jewish fundamentalism, which presents the cultural proposition that Israel's mistreatment of the Palestinians is rooted in a Judaic requirement (of permission) for Jews to commit crimes, including murder, against Gentiles (non-Jews). In his foreword, Said said that Jewish History, Jewish Religion is "nothing less than a concise history of classic and modern Judaism, insofar as these are relevant to the understanding of modern Israel"; and praised the historian Shahak for describing contemporary Israel as a nation subsumed in a "Judeo–Nazi" cultural ambiance that allowed the dehumanization of the Palestinian Other:[74]

In all my works, I remained fundamentally critical of a gloating and uncritical nationalism. ... My view of Palestine ... remains the same today: I expressed all sorts of reservations about the insouciant nativism, and militant militarism of the nationalist consensus; I suggested, instead, a critical look at the Arab environment, Palestinian history, and the Israeli realities, with the explicit conclusion that only a negotiated settlement, between the two communities of suffering, Arab and Jewish, would provide respite from the unending war.[75]

In 1998, Said made In Search of Palestine (1998), a BBC documentary film about Palestine, past and present. In the company of his son, Wadie, Said revisited the places of his boyhood, and confronted injustices meted out to ordinary Palestinians in the contemporary West Bank. Despite the social and cultural prestige afforded to BBC cinema products in the U.S., the documentary was never broadcast by any American television company.[76][77]

Lebanon stone-throwing incident

On 3 July 2000, whilst touring the Middle East with his son, Wadie, Said was photographed throwing a stone across the Blue Line Lebanese–Israel border, which image elicited much political criticism about his action demonstrating an inherent, personal sympathy with terrorism; and, in Commentary magazine, the journalist Edward Alexander labelled Said as "The Professor of Terror", for aggression against Israel.[78] Said explained the stone-throwing as a two-fold action, personal and political; a man-to-man contest-of-skill, between a father and his son, and an Arab man's gesture of joy at the end of the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon (1985–2000): "It was a pebble; there was nobody there. The guardhouse was at least half a mile away."[79]

Said described the incident as trivial and said that he "threw the stone as a symbolic act" into "an empty place". The Beirut newspaper As-Safir (The Ambassador) interviewed a Lebanese local resident who said that Said was less than ten metres (ca. 30 ft.) from the Israel Defense Force (IDF) soldiers manning the two-storey guardhouse, when he threw the stone, which hit the barbed wire fence in front of the guardhouse.[80] In the U.S., Said's action was criticised by some students at Columbia University and the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith International (Sons of the Covenant). The university provost published a five-page letter stating that Said's action was protected under academic freedom: "To my knowledge, the stone was directed at no-one; no law was broken; no indictment was made; no criminal or civil action has been taken against Professor Saïd."[81]

In February 2001, the Freud Society in Austria cancelled a lecture by Said due to the stone-throwing incident.[82] The President of the Freud Society said "[t]he majority [of the society] decided to cancel the Freud lecture to avoid an internal clash. I deeply regret that this has been done to Professor Said".[79]

Criticism of U.S. foreign policy

In the revised edition of Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (1997), Said criticized the Orientalist bias of the Western news media's reportage about the Middle East and Islam, especially the tendency to editorialize "speculations about the latest conspiracy to blow up buildings, sabotage commercial airliners, and poison water supplies."[83] He criticized the American military involvement in the Kosovo War (1998–99) as an imperial action; and described the Iraq Liberation Act (1998), promulgated during the Clinton Administration, as the political license that predisposed the U.S. to invade Iraq in 2003, which was authorised with the Iraq Resolution (2 October 2002); and the continual support of Israel by successive U.S. presidential governments, as actions meant to perpetuate regional political instability in the Middle East.[15]

In the event, despite being sick with leukemia, as a public intellectual, Said continued criticising the U.S. Invasion of Iraq in mid-2003;[84] and, in the Egyptian Al-Ahram Weekly newspaper, in the article "Resources of Hope" (2 April 2003), Said said that the U.S. war against Iraq was a politically ill-conceived military enterprise.[85]

Under FBI surveillance

In 2003, Haidar Abdel-Shafi, Ibrahim Dakak, Mustafa Barghouti, and Said established Al-Mubadara (the Palestinian National Initiative), headed by Barghouti, a third-party reformist, democratic party meant to be an alternative to the usual two-party politics of Palestine. Its ideology is to be an alternative to the extremist politics of the social-democratic Fatah and the Islamist Hamas. Said's founding of the group, as well as his other international political activities concerning Palestine, were noticed by the U.S. government, and Said came under FBI surveillance, which became more intensive after 1972. David Price, an anthropologist at Evergreen State College, requested the FBI file on Said through the Freedom of Information Act on behalf of CounterPunch and published a report there on his findings.[86] The released pages of Said's FBI files show that the FBI read Said's books and reported on their contents to Washington.[87]: 158 [88]

Musical interests

Besides having been a public intellectual, Edward Said was an accomplished pianist, worked as the music critic for The Nation magazine, and wrote four books about music: Musical Elaborations (1991); Parallels and Paradoxes: Explorations in Music and Society (2002), with Daniel Barenboim as co-author; On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (2006); and Music at the Limits (2007) in which final book he spoke of finding musical reflections of his literary and historical ideas in bold compositions and strong performances.[89][90]

Elsewhere in the musical world, the composer Mohammed Fairouz acknowledged the deep influence of Edward Said upon his works; compositionally, Fairouz's First Symphony thematically alludes to the essay "Homage to a Belly-Dancer" (1990), about Tahia Carioca, the Egyptian dancer, actress, and political militant; and a piano sonata, titled Reflections on Exile (1984), which thematically refers to the emotions inherent to being an exile.[91][92][93]

West–Eastern Divan Orchestra

In 1999, Said and Barenboim co-founded the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, composed of young Israeli, Palestinian, and Arab musicians. They also established The Barenboim–Said Foundation in Seville, to develop education-through-music projects. Besides managing the West–Eastern Divan Orchestra, the Barenboim–Said Foundation assists with the administration of the Academy of Orchestral Studies, the Musical Education in Palestine Project, and the Early Childhood Musical Education Project, in Seville.[94]

Honors and awards

Besides honors, memberships, and postings to prestigious organizations worldwide, Edward Said was awarded some twenty honorary university degrees in the course of his professional life as an academic, critic, and Man of Letters.[95] Among the honors bestowed to him were:

- the Bowdoin Prize by Harvard University.

- He twice received the Lionel Trilling Book Award; the first occasion was the inaugural bestowing of said literary award in 1976, for Beginnings: Intention and Method (1974). He also received the

- Wellek Prize of the American Comparative Literature Association

- The inaugural Spinoza Lens Prize.[96]

- Lannan Literary Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2001

- Prince of Asturias Award for Concord in 2002 (shared with Daniel Barenboim).

- First U.S. citizen to receive the Sultan Owais Prize (for Cultural & Scientific Achievements, 1996–1997).[97]

- The autobiography Out of Place (1999)[19] was bestowed three awards, the 1999 New Yorker Book Award for Non-Fiction; the 2000 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Non-Fiction; and the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award in Literature.[98]

Death and legacy

On 24 September 2003, after enduring a 12-year sickness with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Said died, at 67 years of age, in New York City.[12] He is survived by his wife, Mariam C. Said,[99] his son, Wadie Said, and his daughter, Najla Said.[100][101][102] The eulogists included Alexander Cockburn ("A Mighty and Passionate Heart");[103] Seamus Deane ("A Late Style of Humanism");[104] Christopher Hitchens ("A Valediction for Edward Said");[105] Tony Judt ("The Rootless Cosmopolitan");[106] Michael Wood ("On Edward Said");[72] and Tariq Ali ("Remembering Edward Said, 1935–2003").[107] Said is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Broumana, Jabal Lubnan, Lebanon.[108][109][110] His headstone indicates he died on 25 September 2003.

The tributes to Said include books and schools. The books include Waiting for the Barbarians: A Tribute to Edward W. Said (2008) that features essays by Akeel Bilgrami, Rashid Khalidi, and Elias Khoury;[111][112] Edward Said: The Charisma of Criticism (2010), by Harold Aram Veeser, a critical biography; and Edward Said: A Legacy of Emancipation and Representations (2010), with essays by Joseph Massad, Ilan Pappé, Ella Shohat, Ghada Karmi, Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, and Daniel Barenboim.

In 2002, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nayhan, the founder and president of the United Arab Emirates, and others endowed the Edward Said Chair at Columbia University; it is currently filled by Rashid Khalidi.[113][114]

In November 2004, in Palestine, Birzeit University renamed their music school the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music.[115]

The Barenboim–Said Academy (Berlin) was established in 2012.

In 2016, California State University, Fresno started examining applicants for a newly created Professorship in Middle East Studies named after Edward Said, but after months of examining applicants, Fresno State canceled the search. Some observers claim that the cancellation was due to pressure from pro-Israeli individuals and groups.[116]

References

Notes

- ^ /sɑːˈiːd/; Arabic: إدوارد وديع سعيد, romanized: Idwārd Wadīʿ Saʿīd, [wædiːʕ sæʕiːd]

Citations

- ^ a b c "Edward Said". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 16 February 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ a b Robert Young, White Mythologies: Writing History and the West, New York & London: Routledge, 1990.

- ^ Ferial Jabouri Ghazoul, ed. (2007). Edward Saïd and Critical Decolonization. American University in Cairo Press. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-977-416-087-5. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

Edward W. Saïd (1935–2003) was one of the most influential intellectuals in the twentieth century.

- ^ Zamir, Shamoon (2005), "Saïd, Edward W.", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), Encyclopedia of Religion, Second Edition, vol. 12, Macmillan Reference USA, Thomas Gale, pp. 8031–32,

Edward W. Saïd (1935–2003) is best known as the author of the influential and widely-read Orientalism (1978) ... His forceful defense of secular humanism and of the public role of the intellectual, as much as his trenchant critiques of Orientalism, and his unwavering advocacy of the Palestinian cause, made Saïd one of the most internationally influential cultural commentators writing out of the United States in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

- ^ Gentz, Joachim (2009). "Orientalism/Occidentalism". Keywords re-oriented. interKULTUR, European-Chinese intercultural studies, Volume IV. Universitätsverlag Göttingen. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-3-940344-86-1. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

Edward Saïd's influential Orientalism (1979) effectively created a discursive field in cultural studies, stimulating fresh critical analysis of Western academic work on "The Orient". Although the book, itself, has been criticized from many angles, it is still considered to be the seminal work to the field.

- ^ Richard T. Gray; Ruth V. Gross; Rolf J. Goebel; Clayton Koelb, eds. (2005). A Franz Kafka encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-0-313-30375-3. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

In its current usage, Orient is a key term of cultural critique that derives from Edward W. Saïd's influential book Orientalism.

- ^ a b c Stephen Howe, "Dangerous mind?", New Humanist, Vol. 123, November/December 2008.

- ^ "Between Worlds", Reflections on Exile, and Other Essays (2002) pp. 561, 565.

- ^ Sherry, Mark (2010). "Said, Edward Wadie". In John R. Shook (ed.). Said, Edward Wadie (1935–2003). The Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers. Oxford: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-19-975466-3.

- ^ a b Ian Buchanan, ed. (2010). "Said, Edward". A Dictionary of Critical Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953291-9.

- ^ a b Dr. Farooq, Study Resource Page Archived 9 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Global Web Post. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Richard (26 September 2003). "Edward W. Said, Literary Critic and Advocate for Palestinian Independence, Dies at 67". The New York Times. p. 23. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Andrew N. Rubin,"Edward W. Said", Arab Studies Quarterly, Fall 2004: p. 1. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Said, Edward (10 January 1999). "The One-State Solution". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

Given the collapse of the Netanyahu Government over the Wye peace agreement, it is time to question whether the entire process begun in Oslo in 1993 is the right instrument for bringing peace between Palestinians and Israelis. It is my view that the peace process has in fact put off the real reconciliation that must occur if the hundred-year war between Zionism and the Palestinian people is to end. Oslo set the stage for separation, but real peace can come only with a binational Israeli–Palestinian state.

- ^ a b Democracy Now!, "Edward Saïd Archive", DemocracyNow.org, 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2010. Archived 8 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Sherry, Mark (2005). Shook, John R. (ed.). Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers. Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum. p. 2106. ISBN 9781843710370.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (21 June 1993). "Envoy to Two Cultures". Time. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ "Edward Said". This Week in Palestine. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Said, Edward W. (1999). Out of Place. Vintage Books, NY.

- ^ "Edward Said: 'Out of Place'", 14 November 2018, Aljazeera.com. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Piterberg, Gabriel (27 September 2003). "Edward Wadie Said a political activist literary critic". The Independent. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Narrativising Illness: Edward Said's Out of Place and the Postcolonial Confessional/Indisposed Self". Arab World English Journal. p. 10.

- ^ Ihab Shalback, 'Edward Said and the Palestinian Experience,' in Joseph Pugliese (ed.) Transmediterranean: Diasporas, Histories, Geopolitical Spaces, Peter Lang, 2010, pp. 71–83

- ^ "Out of the shadows". The Guardian. 11 September 1999. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Iskander, Adel; Hakem Rustom (2010). Edward Saïd: A Legacy of Emancipation and Representation. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24546-4.

[Edward Wadie] Saïd was of Christian background, a confirmed agnostic, perhaps even an atheist, yet he had a rage for justice and a moral sensibility lacking in most [religious] believers. Saïd retained his own ethical compass without God, and persevered in an exile, once forced, from Cairo, and now chosen, affected by neither malice nor fear.

- ^ Cornwell, John (2010). Newman's Unquiet Grave: The Reluctant Saint. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 128. ISBN 9781441150844.

A hundred and fifty years on, Edward Saïd, an agnostic of Palestinian origins, who strove to correct false Western impressions of 'Orientalism', would declare Newman's university discourses both true and 'incomparably eloquent'. ...

- ^ Sacco, Joe (2001). Palestine. Fantagraphics.

- ^ Amritjit Singh, Interviews With Edward W. Saïd (Oxford: UP of Mississippi, 2004), pp. 19, 219.

- ^ Said, Edward, Defamation, Revisionist Style, CounterPunch, 1999. Retrieved 7 February 2010. Archived 10 December 2002 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Friends rally to repulse attack on Edward Said" by Julian Borger 23 August 1999

- ^ a b c Said, Edward (7 May 1998), "Between Worlds | Edward Said makes sense of his life", London Review of Books. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ Said, Edward William (1957). "The Moral Vision: Andre Gide and Graham Greene". Princeton DataSpace. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b LA Jews For Peace, The Question of Palestine by Edward Saïd. (1997) Books on the Israel–Palestinian Conflict – Annotated Bibliography. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Omri, Mohamed-Salah, "The Portrait of the Intellectual as a Porter"

- ^ Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin, Eds., The Edward Saïd Reader, Vintage, 2000, p. xv.

- ^ "The Reith Lectures: Edward Saïd: Representation of the Intellectual: 1993". BBC. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Said, Edward W. (24 October 2012). Culture and Imperialism. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307829658.

- ^ Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (1966).

- ^ McCarthy, Conor (2010). The Cambridge Introduction to Edward Said. Cambridge UP. pp. 16–. ISBN 9781139491402. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Edward Saïd, Power, Politics and Culture, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001: pp. 77–79.

- ^ a b c Windschuttle, Keith. "Edward Saïd's 'Orientalism revisited'", The New Criterion 17 January 1999. Archived 1 May 2008, at the Internet Archive. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Said, Edward (2003) [Reprinted with a new preface, first published 1978]. Orientalism. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0141187425.

- ^ Kramer, Martin. "Enough Said (Book review: Dangerous Knowledge, by Robert Irwin)", March 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard. "The Question of Orientalism", Islam and the West, London: 1993. pp. 99, 118.

- ^ Irwin, Robert. For Lust of Knowing: The Orientalists and Their Enemies London:Allen Lane: 2006.

- ^ "Said's Splash" Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in America, Policy Papers 58 (Washington, D.C.: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2001).

- ^ Martin Kramer said that "Fifteen years after [the] publication of Orientalism, the UCLA historian Nikki Keddie (whose work Saïd praised in Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World) allowed that Orientalism was 'important, and, in many ways, positive' ".[46]

- ^ Approaches to the History of the Middle East, Nancy Elizabeth Gallagher, Ed., London:Ithaca Press, 1994: pp. 144–45.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (24 June 1982). "The Question of Orientalism" (PDF). New York Review of Books. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ a b Saïd, Edward, "Orientalism Reconsidered", Cultural Critique magazine, No. 1, Autumn 1985, p. 96.

- ^ Eagleton, Terry. Eastern Block (book review of For Lust of Knowing: The Orientalists and Their Enemies, 2006, by Robert Irwin) Archived 18 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, New Statesman, 13 February 2006.

- ^ Kramer, Martin (2001). Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in America.

- ^ Andrew N. Rubin, "Techniques of Trouble: Edward Saïd and the Dialectics of Cultural Philology", The South Atlantic Quarterly, 102.4 (2003). pp. 862–76.

- ^ Emory University, Department of English, Introduction to Postcolonial Studies

- ^ Prakash, Gyan (April 1990). "Writing Post-Orientalist Histories of the Third World: Perspectives from Indian Historiography". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 32 (2): 383–408. doi:10.1017/s0010417500016534. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 178920. S2CID 144435305.

- ^ Nicholas Dirks, Castes of Mind, Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001.

- ^ Ronald Inden, Imagining India, New York: Oxford UP, 1990.

- ^ Simon Springer, "Culture of Violence or Violent Orientalism? Neoliberalisation and Imagining the 'Savage Other' in Post-transitional Cambodia", Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34.3 (2009): 305–19.

- ^ Bhabha, Homi K., Nation and Narration, New York & London: Routledge, Chapman & Hall, 1990.

- ^ Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics, London: Methuen, 1987.

- ^ Ashbrook, John E. (2008). Buying and Selling the Istrian Goat: Istrian Regionalism, Croatian Nationalism, and EU Enlargement. New York: Peter Lang. p. 22. ISBN 978-90-5201-391-6. OCLC 213599021.

Milica Baki–Hayden built on Wolff's work, incorporating the ideas of Edward Saïd's "Orientalism"

- ^ Ethnologia Balkanica. Sofia: Prof. M. Drinov Academic Pub. House. 1995. p. 37. OCLC 41714232.

The idea of "nesting orientalisms", in Baki–Hayden 1995, and the related concept of "nesting balkanisms", in Todorova 1997. ...

- ^ Kamel, Lorenzo (2014). "The Impact of "Biblical Orientalism" in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Palestine". New Middle Eastern Studies (4). Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Masalha, Nur (2007). The Bible and Zionism: Invented Traditions, Archaeology and Post-Colonialism in Palestine–Israel. New York: Zed Books.

- ^ Gandhi, Leela (1998). Postcolonial Theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ "Between Worlds", Reflections on Exile, and Other Essays (2002) pp. 563.

- ^ Saïd, Edward, "Zionism from the Standpoint of its Victims" (1979), in The Edward Saïd Reader, Vintage Books, 2000, pp. 114–68.

- ^ "Imperial Continuity – Palestine, Iraq, and U.S. Policy". YouTube. 8 May 2003. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Ruthven, Nalise (26 September 2003), "Edward Said: Controversial Literary Critic and Bold Advocate of the Palestinian Cause in America", The Guardian. Retrieved 1 March 2006.

- ^ Saïd, Edward (21 October 1993), "The Morning After". London Review of Books, Vol. 15, No. 20.

- ^ Senna, Carl (6 January 2007). "Dis-Oriented". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ a b Wood, Michael (23 October 2003). "On Edward Said". London Review of Books. Vol. 25, no. 20. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022.

- ^ Said, Edward (23 July 2001), "The price of Camp David", Al Ahram Weekly. Retrieved 5 January 2010. Archived 15 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Werner Cohn: What Edward Said knows. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Edward Saïd, "Orientalism, an Afterward" Raritan 14:3 (Winter 1995).

- ^ "In Search of Palestine (1998)". BFI. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018.

- ^ Culture and resistance: conversations with Edward W. Said By Edward W. Said, David Barsamian, p. 57

- ^ a b Julian Vigo, "Edward Saïd and the Politics of Peace: From Orientalisms to Terrorology", A Journal of Contemporary Thought (2004): pp. 43–65.

- ^ a b Dinitia Smith, "A Stone's Throw is a Freudian Slip", The New York Times, 10 March 2001.

- ^ Sunnie Kim, Edward Said Accused of Stoning in South Lebanon, Columbia Spectator, 19 July 2000.

- ^ Karen W. Arenson (19 October 2000). "Columbia Debates a Professor's 'Gesture'". The New York Times.

- ^ Edward Saïd and David Barsamian, Culture and Resistance – Conversations with Edward Said, South End Press, 2003: pp. 85–86

- ^ Martin Kramer, Enough Said review of Dangerous Knowledge, by Robert Irwin, March 2007.

- ^ Democracy Now!, "Syrian Expert Patrick Seale and Columbia University Professor Edward Said Discuss the State of the Middle East After the Invasion of Iraq", DemocracyNow.org, 15 April 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Said, Edward."Resources of Hope", Al-Ahram Weekly, 2 April 2003. Retrieved 26 April 2007. Archived 21 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Price, David (13 January 2006), "How the FBI Spied on Edward Said", CounterPunch. Retrieved 15 January 2006. Archived 16 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Brennan, Timothy (2021). Places of Mind. A Life of Edward Said. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374146535.

- ^ Cockburn, Alexander (12 January 2006). "The FBI and Edward Said". The Nation. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Ranjan Ghosh, Edward Said and the Literary, Social, and Political World, New York: Routledge, 2009: p. 22. Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Columbia University Press, Music at the Limits by Edward W. Saïd. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Rase, Sherri (8 April 2011), Conversations—with Mohammed Fairouz Archived 22 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, [Q]onStage. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Homage to a Belly-dancer", Granta, 13 (Winter 1984).

- ^ "Reflections on Exile", London Review of Books, 13 September 1990.

- ^ Barenboim–Saïd Foundation, official website Archived 27 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Barenboim-Said.org. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ The English Pen World Atlas, "Edward Said" Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Spinozalens, Internationale Spinozaprijs Laureates Archived 5 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Columbia University Press, "About the Author", Humanism and Democratic Criticism, 2004.

- ^ The English Pen World Atlas, Edward Said Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Saeed, Saeed (1 April 2019). "Life beyond Edward: how Mariam Said is carving her own legacy". The National. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Ruthven, Malise (26 September 2003). "Obituary: Edward Said". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Columbia Community Mourns Passing of Edward Said, Beloved and Esteemed University Professor". Office of Public Affairs. Columbia News. Columbia University. 26 September 2003. Archived from the original on 2 October 2003. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Feeney, Mark (26 September 2003). "Edward Said, critic, scholar, Palestinian advocate; at 67". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Cockburn, Alexander (25 September 2003). "Edward Said: A Mighty and Passionate Heart". CounterPunch. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022.

- ^ Deane, Seamus (2005). "Edward Said (1935–2003): A Late Style of Humanism" (PDF). Field Day Review. 1: 189–202. ISSN 1649-6507. JSTOR 30078611. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2022.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (26 September 2003). "A valediction for Edward Said". Slate. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023.

- ^ Judt, Tony (1 July 2004). "The Rootless Cosmopolitan". The Nation (published 19 July 2004). Archived from the original on 25 January 2022.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (2003). "Remembering Edward Said, 1935–2003". New Left Review. 24: 59–65. ISSN 0028-6060. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Edward Said to be buried in Lebanon". Al Jazeera. 2 October 2003. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Ashes of Edward Said Buried in Lebanon". Tehran Times. 1 November 2003. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Said to be buried in Lebanon". DAWN.COM. 3 October 2003. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Conference: Waiting for the Barbarians: A Tribute to Edward Said." Archived 13 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine 25–26 May 2007. Bogazici University. European Journal of Turkish Studies. Ejts.org. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Jorgen Jensehausen, "Review: 'Waiting for the Barbarians'" Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 46, No. 3 May 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Fish, Rachel (2010). "Standing up for Academic Integrity on Campus". In Pollack, Eunice G. (ed.). Antisemitism on the Campus: Past and Present. Boston: Academic Studies Press. p. 376. ISBN 9781618110428.

- ^ "Khalidi, Rashid". Department of History – Columbia University. 2 September 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Birzeit University, Edward Said National Conservatory of Music.

- ^ Flaherty, Colleen (31 May 2017). "Why did Fresno State cancel a search for a professorship named after the late Edward Said?". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

Sources

- Barsamian, David (2003). Culture and Resistance: Conversations with Edward W. Said. Pluto. ISBN 9780745320175.

- Brennan, Timothy (2021). Places of Mind. A Life of Edward Said. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374146535.

- Cornwell, John (2010). Newman's Unquiet Grave: The Reluctant Saint. Continuum International. ISBN 9781441150844.

- Gentz, Joachim (2009). "Orientalism/Occidentalism". Keywords re-oriented. interKULTUR, European-Chinese intercultural studies, Volume IV. Universitätsverlag Göttingen. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-3-940344-86-1. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Ghazoul, Ferial Jabouri, ed. (2007). Edward Said and Critical Decolonization. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-087-5. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

Edward W. Said (1935–2003) was one of the most influential intellectuals in the twentieth century.

- Gray, Richard T.; Gross, Ruth V.; Goebel, Rolf J.; et al., eds. (2005). A Franz Kafka encyclopedia. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-30375-3. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Iskander, Adel; Rustom, Hakem (2010). Edward Said: A Legacy of Emancipation and Representation. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24546-4.

- McCarthy, Conor (2010). The Cambridge Introduction to Edward Said. Cambridge UP. ISBN 9781139491402.

- Said, Edward W. (1979). Orientalism. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 9780394740676.

- Said, Edward W. (1996). Peace and Its Discontents: Essays on Palestine in the Middle East Peace Process. Vintage Books. ISBN 9780679767251.

- Singh, Amritjit; Johnson, Bruce G., eds. (2004). Interviews with Edward W. Said. UP of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578063666.

- Turner, Bryan S; Rojek, Chris (2001). Society and Culture: Scarcity and Solidarity. SAGE. ISBN 9780761970491.

- Zamir, Shamoon (2005). "Said, Edward W.". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion, Second Edition. Vol. 12. Macmillan. pp. 8031–32.

Further reading

- Brennan, Timothy. Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said (2021). online review

- Kennedy, Valerie. Edward Said: A Critical Introduction. Key Contemporary Thinkers. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000.

- McCarthy, Conor. The Cambridge Introduction to Edward Said. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Pannian, Prasad (20 January 2016). Edward Said and the Question of Subjectivity. New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137548641. Edward Said and the Question of Subjectivity at Google Books.

- Rubin, Andrew N. ed. Humanism, Freedom, and the Critic: Edward W. Said and After. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2005.

- Said, Edward W. Moustafa Bayoumi, et al. The Selected Works of Edward Said, 1966 – 2006 (2019) excerpt

External links

- Edward Said, 2000: "My Encounter with Sartre", London Review of Books.

- Edward Said at IMDb

- Review of Reflections on Exile and Other Essays and Edward Said: The Last Interview, in Other Voices, vol. 3, no. 1.

- Works by Edward Said at Open Library

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Finding aid to Edward Said papers at Columbia University – Rare Book & Manuscript Library

- 1935 births

- 2003 deaths

- Edward Said

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- Academics from Jerusalem

- American activists

- American agnostics

- American Book Award winners

- American humanists

- American literary critics

- American male non-fiction writers

- American philosophers

- American political writers

- American writers of Lebanese descent

- American writers of Palestinian descent

- Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences fellows

- Columbia University faculty

- Deaths from leukemia in New York (state)

- Harvard University alumni

- Islam and politics

- Middle Eastern studies in the United States

- Northfield Mount Hermon School alumni

- Orientalism

- Palestinian activists

- Palestinian agnostics

- Palestinian literary critics

- Palestinian people of Lebanese descent

- Palestinian philosophers

- Palestinian political writers

- Postcolonial literature

- Presidents of the Modern Language Association

- Princeton University alumni

- Said family

- Scholars of nationalism

- St. George's School, Jerusalem alumni

- The Nation (U.S. magazine) people