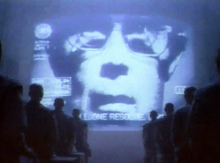

1984 (advertisement)

| "1984" | |

|---|---|

Still image from the advertisement | |

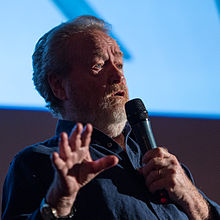

| Directed by | Ridley Scott |

| Written by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Adrian Biddle |

| Edited by | Pamela Power |

Production companies | Fairbanks Films, New York |

| Distributed by | Apple Computer Inc. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 1 minute |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $370,000 – $900,000 |

"1984" is an American television commercial that introduced the Apple Macintosh personal computer. It was conceived by Steve Hayden, Brent Thomas, and Lee Clow at Chiat/Day, produced by New York production company Fairbanks Films, and directed by Ridley Scott. The ad was a reference to George Orwell's noted 1949 novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which described a dystopian future ruled by a televised "Big Brother".[1] English athlete Anya Major performed as the unnamed heroine and David Graham as Big Brother.[2] In the US, it first aired in 10 local outlets,[3] including Twin Falls, Idaho, where Chiat/Day ran the ad on December 31, 1983, at the last possible break before midnight on KMVT, so that the advertisement qualified for the 1984 Clio Awards.[4][5][6] Its second televised airing, and only US national airing, was on January 22, 1984, during a break in the third quarter of the telecast of Super Bowl XVIII by CBS.[7]

In one interpretation of the commercial, "1984" used the unnamed heroine to represent the coming of the Macintosh (indicated by her white tank top with a stylized line drawing of Apple’s Macintosh computer on it) as a means of saving humanity from "conformity" (Big Brother).[8]

Originally a subject of contention within Apple, it has subsequently been called a watershed event[9] and a masterpiece[10] in advertising. In 1995, The Clio Awards added it to its Hall of Fame, and Advertising Age placed it on the top of its list of 50 greatest commercials.[11]

Plot

[edit]The commercial opens with a dystopian, industrial setting in blue and grayish tones, showing a line of people marching in unison through a long tunnel monitored by a string of telescreens. This is in sharp contrast to the full-color shots of the nameless runner (Anya Major). She looks like a competitive track and field athlete, wearing an athletic outfit (red athletic shorts, running shoes, a white tank top with a cubist picture of Apple's Macintosh computer, a white sweat band on her left wrist, and a red one on her right), and is carrying a large brass-headed sledgehammer.[12] Rows of marching minions evoke the opening scenes of Metropolis.

As she is chased by four police officers (presumably agents of the Thought Police) wearing black uniforms, protected by riot gear, helmets with visors covering their faces, and armed with large night sticks, she races towards a large screen with the image of a Big Brother-like figure (David Graham, also seen on the telescreens earlier) giving a speech:

Today, we celebrate the first glorious anniversary of the Information Purification Directives. We have created, for the first time in all history, a garden of pure ideology—where each worker may bloom, secure from the pests purveying contradictory thoughts. Our Unification of Thoughts is more powerful a weapon than any fleet or army on earth. We are one people, with one will, one resolve, one cause. Our enemies shall talk themselves to death, and we will bury them with their own confusion. We shall prevail!

The runner, now close to the screen, hurls the hammer towards it, right at the moment Big Brother announces, "we shall prevail!" In a flurry of light and smoke, the screen is destroyed, leaving the audience in shock.

The commercial concludes with a portentous voiceover by actor Edward Grover, accompanied by scrolling black text (in Apple's early signature Garamond typeface); the hazy, whitish-blue aftermath of the cataclysmic event serves as the background. It reads:

On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like "1984".

The screen fades to black as the voiceover ends, and the rainbow Apple logo appears.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

The commercial was created by the advertising agency Chiat/Day, of Venice, California, with copy by Steve Hayden,[13] art direction by Brent Thomas, and creative direction by Lee Clow.[14] The commercial "grew out of an abandoned print campaign" with a specific theme:[3]

"[T]here are monster computers lurking in big business and big government that know everything from what motels you've stayed at to how much money you have in the bank. But at Apple we're trying to balance the scales by giving individuals the kind of computer power once reserved for corporations."

Ridley Scott (whose dystopian sci-fi film Blade Runner had been released one and a half years prior) was hired by agency producer Richard O'Neill to direct it. Less than two months after the Super Bowl airing, The New York Times reported that Scott "filmed it in England for about $370,000";[3] In 2005 writer Ted Friedman said the commercial had a then-"unheard-of production budget of $900,000."[15] The actors who appeared in the commercial were paid $25 per day.[16] Scott later admitted that he accepted brutal budget constraints because he believed in the ad's concept, outlining how the total cost was less than $250,000 and that he used local skinheads to portray the broken, pale "drones" in the commercial.[17]

Steve Jobs and John Sculley were so enthusiastic about the final product that they "...purchased one and a half minutes of ad time for the Super Bowl, annually the most-watched television program in America. In December 1983 they screened the commercial for the Apple Board of Directors. To Jobs' and Sculley's surprise, the entire board hated the commercial."[15][18][19] However, Sculley himself got "cold feet" and asked Chiat/Day to sell off the two commercial spots.[20]

Despite the board's dislike of the film, Steve Wozniak and others at Apple showed copies to friends, and he offered to pay for half of the spot personally if Jobs paid the other half.[19] This turned out to be unnecessary. Of the original ninety seconds booked, Chiat/Day resold thirty seconds to another advertiser, then claimed they could not sell the other 60 seconds, when in fact they did not even try.[21]

Intended message

[edit]In his 1983 Apple keynote address, Steve Jobs read the following story before showcasing a preview of the commercial:[22]

"[...] It is now 1984. It appears IBM wants it all. Apple is perceived to be the only hope to offer IBM a run for its money. Dealers initially welcoming IBM with open arms now fear an IBM dominated and controlled future. They are increasingly turning back to Apple as the only force that can ensure their future freedom. IBM wants it all and is aiming its guns on its last obstacle to industry control: Apple. Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right about 1984?"

In March 1984 Michael Tyler, a communications expert quoted by The New York Times, said "The Apple ad expresses a potential of small computers. This potential may not automatically flow from the company's product. But if enough people held a shared intent, grass-roots electronic bulletin boards (through which computer users share messages) might result in better balancing of political power."[3]

In 2004, Adelia Cellini writing for Macworld, summarized the message:[8]

"Let's see—an all-powerful entity blathering on about Unification of Thoughts to an army of soulless drones, only to be brought down by a plucky, Apple-esque underdog. So Big Brother, the villain from Apple's '1984' Mac ad, represented IBM, right? According to the ad's creators, that's not exactly the case. The original concept was to show the fight for the control of computer technology as a struggle of the few against the many, says TBWA/Chiat/Day's Lee Clow. Apple wanted the Mac to symbolize the idea of empowerment, with the ad showcasing the Mac as a tool for combating conformity and asserting originality. What better way to do that than have a striking blonde athlete take a sledgehammer to the face of that ultimate symbol of conformity, Big Brother?"

Reception and legacy

[edit]

Art director Brent Thomas said Apple "had wanted something to 'stop America in its tracks, to make people think about computers, to make them think about Macintosh.' With about $3.5 million worth of Macintoshes sold just after the advertisement ran, Thomas judged the effort 'absolutely successful.' 'We also set out to smash the old canard that the computer will enslave us,' he said. 'We did not say the computer will set us free—I have no idea how it will work out. This was strictly a marketing position.'"[3]

The estate of George Orwell and the television rightsholder to the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four considered the commercial to be a copyright infringement and sent a cease-and-desist letter to Apple and Chiat/Day in April 1984.[1]

Awards

[edit]- 1984: Clio Awards

- 1984: 31st Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival—Grand Prix[23]

- 1995: Clio Awards—Hall of Fame

- 1995: Advertising Age—Greatest Commercial[11]

- 1999: TV Guide—Number One Greatest Commercial of All Time[24]

- 2003: WFA—Hall of Fame Award (Jubilee Golden Award)

- 2007: Best Super Bowl Spot (in the game's 40-year history)[25]

It ranked at number 38 in Channel 4's 2000 list of the "100 Greatest TV Ads".[26]

Social impact

[edit]Ted Friedman, in his 2005 text, Electric Dreams: Computers in American Culture, notes the impact of the commercial:

- Super Bowl viewers were overwhelmed by the startling ad. The ad garnered millions of dollars worth of free publicity, as news programs rebroadcast it that night. It was quickly hailed by many in the advertising industry as a masterwork. Advertising Age named it the 1980s Commercial of the Decade, and it continues to rank high on lists of the most influential commercials of all time [...] '1984' was never broadcast again, adding to its mystique.[15]

The "1984" ad became a signature representation of Apple computers. It was scripted as a thematic element in the 1999 docudrama, Pirates of Silicon Valley, which explores the rise of Apple and Microsoft (the film opens and closes with references to the commercial, including a re-enactment of the heroine running towards the screen of Big Brother and clips of the original commercial).[27]

The commercial was also prominent in the 20th anniversary celebration of the Macintosh in 2004, as Apple reposted a new version of the ad on its website and showed it during Jobs's Keynote Address at Macworld Expo in San Francisco, California. In this updated version, an iPod, complete with signature white earbuds, was digitally added to the heroine. Keynote Attendees were given a poster showing the heroine with an iPod as a commemorative gift.[28] And the ad has also been cited as the turning point for Super Bowl commercials, which had been important and popular before (especially Coca-Cola's "Hey Kid, Catch!" featuring "Mean" Joe Greene during Super Bowl XIV) but after "1984" those ads became the most expensive, creative and influential advertising set for all television coverage.

Revisiting the commercial in Harper's Magazine thirty years after it aired, social critic Rebecca Solnit suggested that "1984" did not so much herald a new era of liberation as a new era of oppression. In the December 2014 issue of the magazine, she wrote:

I want to yell at that liberatory young woman with her sledgehammer: "Don't do it!" Apple is not different. That industry is going to give rise to innumerable forms of triviality and misogyny, to the concentration of wealth and the dispersal of mental concentration. To suicidal, underpaid Chinese factory workers whose reality must be like that of the shuffling workers in the commercial. If you think a crowd of people staring at one screen is bad, wait until you have created a world in which billions of people stare at their own screens even while walking, driving, eating in the company of friends—all of them eternally elsewhere."[29]

Media archivist (and early Apple supporter) Marion Stokes recorded the Super Bowl broadcast featuring the legendary ad, which was then featured in the 2019 documentary film Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project.[30][31][32]

Parodies

[edit]In 2001, the Futurama season 3 episode Future Stock parodies the advert as a Planet Express advert challenging the all-powerful "MomCorp". In the advert a Planet Express employee throws a delivery package into the telescreen showing Mom - however in contrast to the original advert, after the screen is smashed an annoyed prole turns to the employee and shouts "Hey - we were watching that!"[33][34][35]

In March 2007, the advertisement attracted attention again when Hillary 1984, a video mashup of the original commercial with footage of Hillary Clinton used in place of Big Brother, went viral in the early stages of the campaign for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination. The video was produced in support of Barack Obama by Phil de Vellis, an employee of Blue State Digital, but was made without the knowledge of either Obama's campaign or his own employer. De Vellis stated that he made the video in one afternoon at home using a Mac and some software. Political commentators including Carla Marinucci and Arianna Huffington, as well as de Vellis himself, suggested that the video demonstrated the way technology had created new opportunities for individuals to make an impact on politics.[36][37][38]

The 2008 The Simpsons episode "MyPods and Boomsticks" parodies the ad. In it, Comic Book Guy throws a sledgehammer at a giant screen that displays the CEO "Steve Mobs".[39][40]

In May 2010, Valve released a short video announcing the release of Half-Life 2 on OS X featuring a recreation of the original commercial, with the people replaced with City 17's citizens, Big Brother with a speech from Wallace Breen, the agents of the Thought Police with Combine Soldiers, and the nameless runner with Alyx Vance.[41] It is Valve's only official Half-Life 2 SFM.

In the 2016 The Simpsons episode "The Last Traction Hero", Lisa Simpson is a bus monitor and fantasizes about being on a big screen controlling the bus children with Bart Simpson as the runner with the hammer.[42]

On August 13, 2020, Apple removed Fortnite from the App Store after Epic Games introduced a direct payment option that circumvented Apple's 30% revenue cut policy, violating terms of service policies. In response, Epic filed a lawsuit against Apple, and created a parody of the "1984" ad called "Nineteen Eighty-Fortnite".[43][44]

The 2024 Pixar animated film Inside Out 2 contains a loose parody of the ad, in which the character Joy riles up the Mind Workers to rebel against Anxiety; one worker throws a chair at the giant screen Anxiety uses to monitor their work.[45]

See also

[edit]- Lemmings (advertisement), the follow-up advert

- Think Different, an Apple advertising slogan

- Get a Mac, television advertising campaign

- List of Super Bowl commercials

References

[edit]- ^ a b Coulson, William R. (Winter 2009). "'Big Brother' is Watching Apple: The Truth About the Super Bowl's Most Famous Ad" (PDF). Dartmouth Law Journal. 7 (1): 106–115. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Graham, David. "David's film appearances". David Graham Official Site. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Burnham, David (March 4, 1984). "The Computer, the Consumer and Privacy". The New York Times. Washington DC. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Dougherty, Philip H. (May 24, 1984). "ADVERTISING; Ally & Gargano Prevails At Clio Awards Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ "The True Story of Apple's '1984' Ad's First Broadcast...Before the Super Bowl". mental_floss. February 4, 2012. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Hertzfeld, Andy (September 2004). "1984". Folklore.org. p. 73. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ Friedman, Ted (October 1997). "Apple's 1984: The Introduction of the Macintosh in the Cultural History of Personal Computers". Archived from the original on October 5, 1999.

- ^ a b Cellini, Adelia (January 2004). "The Story Behind Apple's '1984' TV commercial: Big Brother at 20". MacWorld. 21 (1): 18. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Maney, Kevin (January 28, 2004). "Apple's '1984' Super Bowl Commercial Still Stands as Watershed Event". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 10, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (February 3, 2006). "Why 2006 Isn't like '1984'". CNN. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Elliott, Stuart (March 14, 1995). "The Media Business: Advertising; A new ranking of the '50 best' television commercials ever made". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

The choice for the greatest commercial ever was the spectacular spot by Chiat/Day, evocative of the George Orwell novel 1984, that introduced the Apple Macintosh computer during Super Bowl XVIII in 1984.

- ^ Moriarty, Sandra. "An Interpretive Study of Visual Cues in Advertising". University of Colorado. Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Hansen, Liane (February 1, 2004). "A Look Back at Apple's Super Ad". Weekend Edition Sunday. NPR. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ "Lee Clow: His Masterpiece". Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c Friedman, Ted (2005). "Chapter 5: 1984". Electric Dreams: Computers in American Culture. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-2740-9. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Parekh, Rupal (March 29, 2012). "Clow and Hayden Reminisce about Making Apple's '1984'". Advertising Age. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Saul Austerlitz (February 9, 2024). "40 Years Ago, This Ad Changed the Super Bowl Forever". The News York Times.

- ^ Hayden, Steve (January 30, 2011). "'1984': As Good as It Gets". Adweek. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Dvorak, John C. (February 27, 1984). "Apple's stagnation". InfoWorld. p. 112. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2011). Steve Jobs. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.[page needed]

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2011). Steve Jobs. Simon & Schuster. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4516-4853-9.

- ^ "1983 Apple Keynote: The "1984" Ad Introduction". YouTube. April 1, 2006. Archived from the original on June 18, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Dougherty, Philip H. (June 26, 1984). "Advertising; Chiat Wins at Cannes For '1984' Apple Spot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ "TV Guide Names Apple's "1984" Commercial As No. 1 All-Time Commercial!". The Mac Observer. June 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ "Apple's '1984' Named Best Super Bowl Spot". EarthTimes. Retrieved May 10, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Fun Facts". UK TV Adverts. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ Grote, Patrick (October 29, 2006). "Review of Pirates of Silicon Valley Movie". DotJournal.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Tony (January 23, 2004). "The Apple Mac Is 20". The Register. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Solnit, Rebecca (December 2014) "Poison Apples." Harper's. Page 5.

- ^ BAVC1004566_SuperBowl8412284_prores - Internet Archive

- ^ "Let The Record Show|On the Media|WNYC Studios". Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ "A Most Radical TV News Archive|On the Media|WNYC Studios". Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Dormehl, Luke (August 14, 2020). "Fortnite wasn't first: 5 more times Apple's iconic '1984' ad was mocked". Cult of Mac. Retrieved January 17, 2025.

- ^ Caolo, Dave (November 17, 2005). "Futurama's 1984 ad parody on macTV". Retrieved January 17, 2025.

- ^ Chung, Jackson. "(Video) Futurama Spoofs 1984 Apple Commercial". TechEBlog. Retrieved January 17, 2025.

- ^ Marinucci, Carla (March 18, 2007). "Political video smackdown / 'Hillary 1984': Unauthorized Internet ad for Obama converts Apple Computer's '84 Super Bowl spot into a generational howl against Clinton's presidential bid". SFgate.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Huffington, Arianna (March 21, 2007). "Who Created "Hillary 1984"? Mystery Solved!". HuffPost. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ de Vellis, Phil (March 21, 2007). "I Made the "Vote Different" Ad". HuffPost. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Canning, Robert (December 1, 2008). "The Simpsons: "Mypods and Boomsticks" Review". IGN. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ^ Bates, James W.; Gimple, Scott M.; McCann, Jesse L.; Richmond, Ray; Seghers, Christine, eds. (2010). Simpsons World The Ultimate Episode Guide: Seasons 1–20 (1st ed.). Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 972–973. ISBN 978-0-00-738815-8.

- ^ Golijan, Rosa (May 25, 2010). "Valve Parodies Apple's "1984" Commercial". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Malone, Jeffrey (December 5, 2016). "Review: The Simpsons "The Last Traction Hero"". Bubbleblabber. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Fortnite's petty shot in Apple war". NewsComAu. August 13, 2020. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chaim (August 13, 2020). "Epic will mock Apple's most iconic ad as possible revenge for Fortnite's App Store ban". The Verge. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Dubiel, Bill (June 14, 2024). "Inside Out 2's 21 Easter Eggs & Pixar References Explained". ScreenRant. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Clow, Lee. "Lee Clow: His Masterpiece—1984". Chiat/Day. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2004.

- Friedman, Ted (2005). "Chapter Five: Apple's 1984". Electric Dreams: Computers in American Culture. New York: NYU Press. pp. 100–120. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008.

- Roszak, Theodore (January 28, 2004). "Raging Against the Machine: In its '1984' Commercial, Apple Suggested that Its Computers Would Smash Big Brother, But Technology Gave Him More Control". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- Scott, Linda (1991). "For the Rest of Us: A Reader-Oriented Interpretation of Apple's '1984' Commercial". The Journal of Popular Culture. 25 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1991.2501_67.x. S2CID 142199525.

- St. John, Allen (January 13, 2014). "12 Lessons In Creativity From The Greatest Super Bowl Ad Ever". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.